|

Confessions - Concessions - Clarifications - Conclusions:

The author sheds some light on some inventions of the "Great Emile"

by Oliver Berliner

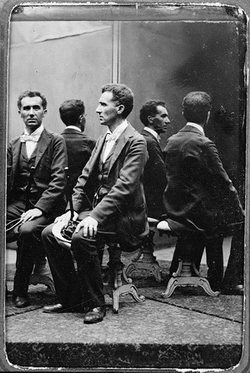

Oliver Berliner attending a CAPS meeting.

Oliver, Noel Martin, Mike Bryan, Domenic DiBernardo. Oct 30, 2011

|

|

As I'm horrified to note that it's been nine years since I

returned to the lands of my birth to visit the CAPS folk,

it's high time I disclosed that, over the years, my positions with respect to certain aspects of grandpa's in-

ventions have changed. I believe that what I propound

here is correct and can possibly be considered the last

words on the matters; and I can thus approach my imminent great reward with a clear conscience.

The Great Emile's first and greatest invention (coming

at age 26) was a kind of telephone that Emile believed

would overcome the shortcomings of Alexander Graham Bell's 1876 telephone. There were other inventors

with the same goal. But what was extraordinary about

the Berliner concept was that it defied the science of

the day, as pronounced by the eminent "electrician",

the Compte du Moncel, that current cannot pass between two electrodes that don't touch each other. Not

knowing he couldn't do it, Emile went and violated the

law of physics. How did he do it?

Emile Berliner’s Microphone

|

|

Simple. The "law" doesn't apply if one of the contacts is

in motion. That aspect of grandpa's telephone was the

missing link that Bell needed to make his own 'phone,

which was sound powered, practical. What Bell

adopted was the transmitter that incorporated battery

power which made possible long-distance telephony,

and an isolation coil that provided amplification while

preventing D.C. voltage from getting to the receiver.

For the sale of this innovation, Emile was paid

US$50,000 in 1878. He declined to take payment in

the form of Bell System shares. [He'd been warned that

Western Union would try to take over telephony.] Had

he done so, his stock, dividends added, would have

been worth One Billion Eighty-six Million Dollars at the

time of the Bell System breakup in 1984. Damn!

Sheet 2

|

|

I've shown Sheet 2 of the Telephone/Telegraph patent.

The dotted lines depict a tube connecting a mouthpiece to the transmitter enclosure (which Emile finally

called a microphone in patent 222,652 of 11 August

1879). P is the coil whose output feeds the receiver.

Emile's initial patent, applied-for June 4, 1877, was not

issued until Nov. 17, 1891 due to interferences by politicians. The Supreme Court, Mr. Justice Brewer presid-

ing, swept aside all interferences, ruling that Bell and

Berliner had done nothing to delay the patent's issuance, further that Emile Berliner was the sole and true

inventor of the microphone.

The toy-drum prototype grandpa used to confirm the

loose-contact principle is likely the one that's in Bell

Canada's archive. The loose-contact (variable resistance) microphone was used for a hundred years in all

the world's telephones. Today its century-old battery

power emanating from each "telco's" central office that still provides the necessary connection to the

world for places where power failures render current-day electronic handsets unusable during a power out-

age. A-men.

And if you fret that in a disaster your landline stops

working, let me tell you that the loss of service is by

decree of your "city fathers" who mistakenly believe

that residents must "stay off" the telephone exactly

when folks need it most, so that emergency personnel

will have clear circuits. Fact is, authorities' circuits are

generally not in the group serving affected areas and

first responders have always had radiotelephones and

never needed to use your lines. Telco landlines virtually

never fail...thanks to Emile Berliner's circuit design.

Emile Berliner

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

|

|

By the way, the U.S Patent Office has opined that its

'most valuable' patent is that of the telephone (by a

Canadian ex-pat), which converted sounds to electrical

pulses and "down the line" (distant) converted the electricity

back to audible sounds. And don't forget that the

Berliner telephone transmitter was the first device to

combine alternating current (sounds converted to electricity) and direct current (battery) in the same circuit;

besides being the first to pass current between electrodes that didn't contact each other.

The Greeks have a word for it.

Before I use any more of them, let's keep in mind (the

English language spelling of) the many Greek words

that have enjoyed common usage in our tight little industry.

telephone - distant sound

microphone - tiny sound

phonautograph - sound signature

phonograph - sound display

graphophone - display of sound

gramophone - sound of words

The Gramophone

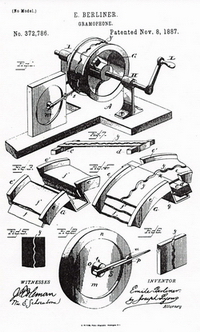

I have always deplored the fact that many cognoscenti

used the phrase, "disc gramophone", when referring to

Emile's best known invention. But the truth is that in

his U.S patent of Nov. 8, 1887 is depicted (Fig. 1) a

cylinder recorder utilizing lateral cut. In this patent

Emile describes his method of mass-producing cylinder

records. As you can see, the recording is on a thin

sheet wrapped around a mandrel. For mass production, the sheet is laid flat and duplicated. You've no

doubt observed that with a wrapped original, or any

copy for playing it, there'd be a click over the joint every

time the mandrel made a complete turn. Fortunately,

grandpa never had to bother with such a cumbersome

and disappointing system - though for patenting, it did

the job. Phew!

But why wasn't the disc gramophone included in the

U.S patent? Simply because Emile was of the belief

that both Bell and Edison's experimentation with discs

(both inventors decided that the cylinder was superior)

precluded his getting a U.S patent. Ho ho.

Fig. 1

|

|

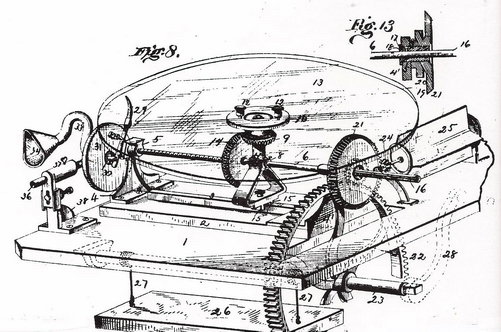

Fig. 8

|

|

We don't get to learn of the disc gramophone until we

encounter British patent 15,232 of the same date,

where Fig. 1 shows the cylinder gramophone recorder/

player. Fig. 8 shows the disc recorder. Note that the

cutting stylus (29) is beneath the disc, allowing the

"chip" (stylus scrapings) to fall away. Emile specifies in

the text that the cutting should start at the inside of the

disc, thus avoiding chip-stylus entanglements. Inside-start was used in radio broadcast transcriptions for

decades, but not in 78s, 33s and 45s for the consumer. Radio transcriptions were sometimes cut vertically. RCA broadcast turntables incorporated a clever

velocity pickup cartridge...effectively a tiny ribbon microphone that tracked laterally- and vertically-cut discs.

Kämmer & Reinhardt Gramophone with metal base

|

|

Emile never recorded on the disc's bottom; but don't

forget that today's Compact Discs, DVDs too, have inside-start, are recorded on one side - the bottom, and

don't use paper labels. [Deutsche Grammophon introduced injection-molded 45s sans paper labels.] CDs

are also mass produced via the Berliner method of

1887...incredible and spectacular, don't you agree? I'd

like to apologize to those whom I disparaged. The

phrase disc gramophone is perfectly proper.

Emile's first Berliner Gramophone Co. was incorporated

in Newark, New Jersey in 1888 so that he'd have convenient access to the Duranoid Co., manufacturer of

large, fancy celluloid buttons for ladies' garments. The

buttons were stamped-out on a press, a process like

what Emile needed in his disc-making process. Discs of

celluloid quickly wore out; rubber discs changed shape.

The business collapsed as did the discs, though not

before grandpa was able to determine that a hot

"biscuit", principally of molten shellac from the Indonesian lac bug, met all requirements of record press and

record player. Now, if only Emile had had the capital to

go on...

Kämmer & Reinhardt Gramophone with wood base

|

|

May I interject that I found in my father's collection the

oldest and rarest disc record in the world - a celluloid

pressing. It's now in the hands of Montreal's Musée

des Ondes Emile Berliner.

At a loss, Emile went back to the "old country" to visit

the world-famous dollmaker, Kämmer & Reinhardt.

Licensing was arranged for them to manufacture

125mm (5") children's records and the toy gramophones on which to play them. They'd be marketed in

Deutschland und England. Emile would produce master recordings for K&R, who'd also produce their own.

Out of this came gems in the Great Emile's still-German

-accented voice: "Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star" and "The

Lord's Prayer".

K&R's first gramophones were iron and weighed more

than a kid could lift. These gave way to a hand-cranked, figure-8 belt-drive unit that was lighter and

prettier. Horns were of gaily painted papier mache'.

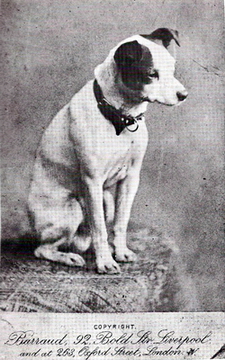

The surviving image of Nipper

from "The Story of Nipper"

|

|

Later, many full-size "figure 8" gramophones (with

metal horn) would enjoy great market acceptance. Because the first production gramophones were for kids,

hearsay among some of today's collectors mistakenly

infers that Emile had created the gramophone as a toy.

Leaping ahead, I also must clarify (without detailing

today the innumerable things that resulted in

the 1901 formation of the Victor Talking Machine Co.

-a long story, as the reader is well aware), that

grandpa did not own nor control the Philadelphia company that bore his name. He'd gotten the long-sought

financing from Thomas Parvin who thus owned 90% of

the firm and ran it, with Emile owning 10% and relying

on patent licensing fees for his compensation. Upon

acquisition by the newly renamed Victor Company,

Emile received Victor shares but played no role in Victor's activities. Parvin got shares and became a Victor

director but not an officer.

It was Emile Berliner who in 1893 trundled over the

bridge of the Delaware River that linked Philly to Camden, New Jersey where he found a struggling machinist

who would create a clockwork motor to power the hand

-crank gramophone. By the time of his retirement at

the end of 1925, Eldridge Reeves Johnson had, in true

rags-to-riches fashion, become one of America's richest

men.

Eldridge Johnson renamed his Consolidated Talking

Machine Co. as Victor to associate the new company

with Emile Berliner's court victory. Confusingly, prior to

the "reorganization" he'd released a record under the

Victor label, named after Victoria, wife of an executive,

a record producer who'd recently joined Consolidated.

E.R.J. called his record players talking machines as he

didn't want to use Emile Berliner's word, gramophone.

The ultimate result of this decision was that in France

and the Americas, gramophones were mistakenly called phonographs. Damn!

"His Master's Voice"

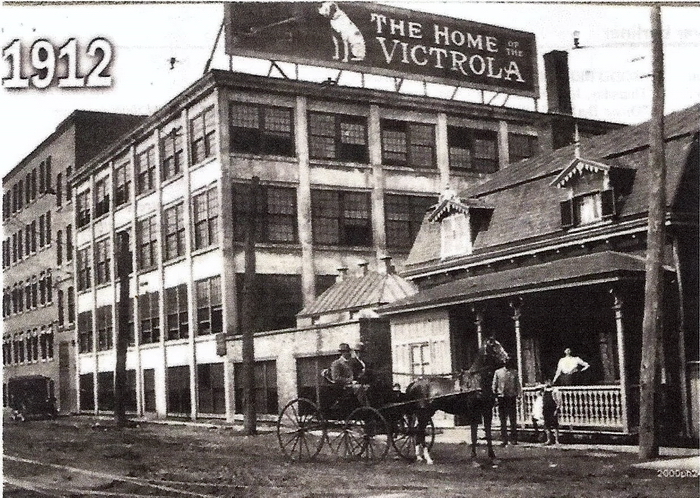

Canada's vastness required the Victor

Company to establish a distribution centre

in Toronto. My father chose to name it His

Master's Voice, Ltd. The new factory that

opened on Lenoir St. in Montreal in 1908

boasted an enormous rooftop sign depicting the world's most famous trade--mark,

seen in a charming 1912 photo. When

launched 1 Jan. 1900, the Berliner Gramophone Co. had pressed records in space

rented from Canadian Bell Telephone Co.

The new facility included a railway siding

where boxcars were loaded with records

and gramophones for shipment to points

north and west. Lenoir St. is now the home

of the Berliner museum. The sign saluting "His Master's

Voice" is long gone. The loading dock and railway

tracks have survived.

The new factory that opened on Lenoir St. in Montreal in 1908

|

|

In year 2000 I picked up CARAS' (Canada's recording

society) award to the Great Emile for his founding of

the country's recorded music industry a century earlier.

I was brought to tears when the audience rose to honour the great man.

From the moment it became a trade-mark, a never-

ending rumour had it that artist Francis Barraud had

depicted the dog, Nipper, sitting on his late master

Mark Barraud's coffin, listening to a recording of

Mark's voice. Today I'm convinced that it truly was a

coffin that Francis had shown - but he thought better of

admitting it. Of course, we know that the dog-with-gramophone was a figment of Francis' imagination;

further that Mark never made a recording.

"His Master’s Voice" painting by Francis Barraud

|

|

It wasn't long after "HMV" had achieved renown that

Francis was accused of copying a photo allowing him to

"remember" Nipper's countenance with such great detail after the dog had been dead some three years. To

sidestep the accusations, he destroyed all photographs

of Nipper...save one: the plate he reversed to make a

print with Nipper facing in the proper direction for his

purposes. "The Story of Nipper..." contains this image -

printed the way it was meant to be.

Francis was years later asked to make as true a copy

of his work as possible, to substitute for the original

which would be hidden away in times of stress. Known

as the "Chinese copy" for its faithfulness to the original,

it was long, long afterwards sent by Gramophone Co.

successor EMI to hang at its Capitol Records subsidiary

in Hollywood. Now EMI itself is gone.

When I saw it, the painting (faithfully revealing the

painted-over Edison-Bell cylinder mandrel and so indistinguishable from the original that it had to be marked

COPY) had special glass over it for protection, as it

hangs in a hallway. EMI eventually made spectacular

lithographs of the painting which the photographer was

asked to shoot in such a way that the overpainting

could be readily seen in the prints.

Francis was also commissioned to make 24 identical,

smaller copies of the original (sans the over-painting).

Bought by Gramophone Co. and Victor Talking Machine

Co., one went to Emile Berliner. As I believe grandpa

brought his model microphone with him to Canada, I

believe he also brought his painting and that his son,

Herbert absconded with it. Herbert and Emile had been

having disagreements over the course the company

should take. On Emile's 1919 visit, Herbert struck his

father, knocking him down.

Oliver Berliner

|

|

Right then, Herbert left the business and was never in

contact with his father or brother again. He spent full

time at his - Decca

Records distributor -

Compo Co. which he'd

formed to compete

with

the

Berliner

Gramophone Co. that

he'd headed. Edgar

succeeded him - in

1924 selling the Company to Victor, becoming president of Victor-

Canada, later of RCA

Victor-Canada.

Emile never completed

those

1919

experiments

in

im-

proving the quality of

disc

mastering.

He

immediately departed

the last vestige of his

companies, as well as

the record business

itself. The remainder of his life was spent solving public

-health issues. He died at 78 at home in Washington, D.C. On August 3, 1929 RCA's National Broadcasting Co. held moments of silence over the network to

signal the passing of Emile Berliner.

Herbert Berliner, his wife Jessie Kerr, and daughter

Katherine

(born,

Montreal

30

Dec.

1915) are all dead.

But where's grandpa's

painting? My guess is

that Katherine's child

or grandchild has it.

Who and where is

that person? Continuing is my $1,000 offer

to anyone who locates the painting.

I hope I've here shed

some light on the

many

mystifying

clashing

concepts

we've long endured;

and that I haven't

made things worse.

Thanx-fer-listnin'.

Ed. note: Berliner established his (second) gramophone

company in Philadelphia for easy access to fotoengraving

inventor Max Levi. Emile used Levi’s process in disc pressing

for "etching the human voice".

|