|

Advertising the Talking Doll in Toronto

by Bill Pratt

Some years ago we bought a delightful, undated, pristine advertisement, printed in Canada, measuring 8 x 11-1/2 inches, which offered an actual 16-inch talking doll, valued at $1.00, FREE for the purchase

of one box of Wrigley's Spearmint Pepsin Gum for 85˘. As phonograph enthusiasts, we naturally associate the phrase "talking doll"

with the Edison phonograph doll which was marketed for several months in 1890, so I wondered about the place of the Wrigley's doll in the history of talking dolls (1)

and whether the phrase was in common usage in Toronto newspapers contemporary with the ad, specifically The Globe and The Evening Star, later named The Toronto Daily Star. The full text of the ad reads:

Collection of Bill and Betty Pratt

|

|

Founded in Chicago in 1891, the Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company has dominated the chewing gum market for more than 100 years. From its earliest days it was a prolific

advertiser, inundating newspapers, magazines and billboards with promotions of its numerous branded products.

Wrigley's principal strategy for keeping its dealers happy was to offer free premiums intended for resale or for the dealer's personal use. (2)

The Wrigley's doll was "sold from jobbers stock only", which implies that 'Advertising Offer "C"' was likely available only to its dealers and not directly to the public.

The offer was issued in 1912 from Wrigley's Canadian factory in Toronto. (3)

The ad assured its recipients that "the smallest dealer can easily dispose of a dozen this time of the year", which suggests a Christmas date for the premium, perhaps December of 1912.

By 1914, Wrigley's had dropped "pepsin" from its advertising - pepsin is an enzyme which aids digestion - and changed its label to "Spearmint: the Perfect Gum". While a thorough on-line search for Wrigley's ads turned up hundreds of examples,

this talking doll promotion was nowhere to be found. It was probably available only in Canada and only for a short time.

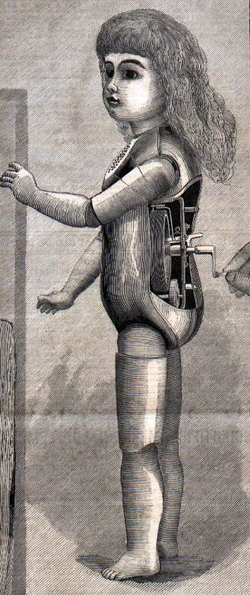

French Musical Automaton

by Leopold Lambert, c. 1890

|

|

What is a "talking doll"? Over the years, the phrase has come to have several meanings. There are numerous documented examples throughout history of man's interest in creating artificial life, or rather, the illusion of life - a figure which

simulates the action of a living being. Automata, or self-operating mechanical devices, are known to have been invented in ancient Greece and ancient China, and human-like machines are known from both Medieval and Renaissance literature.

The 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment, was a golden age in the production of automata. Inspired by an interest in scientific instruments and anatomy, and an aristocratic fondness for toys, inventors created an astonishing range of mechanical

curiosities, notably Jacques de Vaucanson's flute-playing android and a defecating duck, invented in 1737 and 1739 respectively, and Pierre Jaquet-Droz's humanoid automata, exhibited in 1774, capable of drawing pictures and writing poems. Other creations

played tiny reed organs and violins. Singing and flapping birds were ubiquitous.

The first "speaking" automata, which were presented in the guise of talking heads, are attributed to Albertus Magnus and Roger Bacon in the 13th century. In 1778, Wolfgang von Kempelen demonstrated a contrivance that emitted vowel sounds using a hinged box, tube and bellows. The most sophisticated early attempt to mimic the human voice using a mechanical device was the "Euphonia" or "Speaking Machine". Presented by its inventor, Joseph Faber, in Vienna, in 1840, its publication in 1844

may pinpoint the first use of the phrase "talking machine". (4) Although early automata were frequently designed in the image of children, such mechanical marvels were, however, rarely intended

as childs' toys, for obvious reasons. The first use of the phrase "talking doll" is generally recognized to date to an 1824 French patent by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, which described a "talking doll which pronounces the two words papa and maman". (5)

Such novel playthings came to be referred to as "mama" dolls

because they emitted a whiny, wheezy noise that sounded a bit like a baby crying 'mama',

if that baby were a dog’s squeeze toy. The mechanism that made these dolls 'talk' was a lot more basic than Edison’s phonograph (it didn’t use recorded audio) and

actually had its genesis in 19th century Japan, where the first crying baby dolls were sold. Tucked inside each mama doll’s body was a cylindrical bellows device

called a 'crier' or a 'cry box' that drew in air when the bellows expanded and forced it out when it contracted, in a way similar to an accordion. Depending on the

doll, the bellows would be activated by pressing down on the doll or tipping it over. (6)

Edison "talking"

Phonograph doll, 1890

Little Jack Horner,

Little Jack Horner,

Edison talking doll cylinder,

brown wax, solo female voice,

ca February to May 1890

Credit: Smithsonian Institution

|

|

The phrase "talking doll" was used sparingly in early Toronto newspapers. Digitized versions of The Globe are available back to 1844 and The Toronto Star to 1894,

and the phrase appeared just 54 times through 1912, the year of the Wrigley's ad. Notwithstanding its well-established meaning of "mama" doll,

the very first appearance in Toronto newsprint referred to the Edison phonograph doll which was exhibited at the Toronto Industrial Exhibition (TIE) in September, 1890.

Founded in 1879 in Toronto, the TIE, later named the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE), is one of Ontario's great annual traditions. In the July 26, 1890 edition

of The Globe newspaper, in an article titled "The Toronto Industrial: Arrangements for the September Show - New Attractions this Year", there was a

brief notice that "Edison's latest novelty, the talking dolls, have been secured". (7)

The next occurrence of the phrase was a month and a half later on September 13, when the exhibition was in full swing, under the heading "Best Day of the Fair Yet: Thousands of Children on the

Exhibition Grounds":

The Edison talking dolls were on exhibition yesterday for the first time. Manager Hill personally superintended the arrangements for introducing

them to the public. Space was provided at the western end of the upper gallery of the main building, where some young ladies were stationed, each

with one of the dolls, to work the little key which sets the speaking mechanism in motion. One doll repeated Little Jack Horner, another Old Mother

Hubbard, and the others nursery rhymes of almost equal popularity. The utterance of the dolls is keyed very high, and the instruction in each case

having evidently been given by a New England lady, the accent and intonation which the dolls have taken for their model are not the pleasantest or

the best. The dolls were the admiration and wonder of thousands of children during the day, including not a few of the children of larger growth. (8)

Shortly after he had invented the phonograph in 1877, Edison had already envisioned a smaller version for use in clocks and toys. At the Paris exposition of 1878, he exhibited a design for a doll using a mini-phonograph from

which the sound would emerge from a funnel sprouting from the top of the doll's head. Fortunately, this freakish design was abandoned. He revived the concept in the late 1880s, after inventing the light bulb, and marketed a

doll for several months in 1890 which utilized a pre-recorded wax cylinder to simulate the doll's voice. The doll was large and heavy, and the voice was unpleasant and practically unintelligible. Also, the wax cylinder was fragile, easily broken and difficult to replace. It was not a commercial success. It is estimated that only about 500 dolls were sold and only a handful exist today with their phonograph mechanism intact. There are no other firm references to the Edison "talking doll" in early Toronto newspapers.

The next two occurrences of the phrase in Toronto newsprint referenced the more traditional meaning of "talking doll", that of the "mama" doll. The Globe edition of March 5, 1892 published an informative article about a famous doll factory in Paris, noting that:

To make one talking doll requires the joint labor of 30 men. Germany was the first country to invent the talking dolls. So great is the cost of their manufacture

that comparatively few are made. In art, as in nature, it is easier to make a doll baby say "mama" than "papa". (9)

McKendry & Co., The Evening Star,

December 15, 1894, p. 2

|

|

That same year, on November 12, The Globe reported on the visit of a thirteen-year-old African princess named S'Nabou to Paris. Apparently, on her trip from Africa to Europe, when she reached the mouth of the Congo River,

she was presented with a beautiful 'talking wax baby' from Paris. "S'Nabou took it in rapture, but when it suddenly said 'papa! mamma!' she threw it from her in terror and rushed from the room"! (10) Clearly, talking mama dolls were still a rarity

that had not yet reached every corner of the globe.

1894 brought the first two direct advertisements for talking dolls in the Toronto press. The Evening Star edition of December 15 reported:

As long as little girls exist their strongest instinct will point dollward. The reason we have so many good mothers in Canada is because we have so

many little doll lovers in the past. Dolls have come from Japan, England, France, Germany and the States to swell our collection, from a copper up to

many dollars. We fit every pocketbook. Talking Dolls, Sleeping Dolls, Dressed Dolls, dolls of all complexions and sizes. This is emphatically the place

to buy a doll, McKendry & Co. (11)

The same edition advertised a single talking doll for sale for 50 cents at John Milne & Co,. 169 Yonge St. (12)

On December 7, 1895 there appeared the first of many notices of a talking doll by the Robert Simpson Company. Under the heading "For the Children: Splendid Display of

Toys at Simpson's Bazaar - A Talking Doll on Exhibition", The Evening Star reported:

One of the attractions of the big store is a talking doll, the home of which at present is a tent, which has been erected on the second floor, where exhibitions of its prowess will be given. (13)

Bébé Jumeau "talking"

Phonographe doll, 1893

Il Pleut Bergere,

Il Pleut Bergere,

Bébé Jumeau talking doll cylinder,

celluloid, solo female voice, 1896

Credit: The New York Public Library

|

|

Mention of "exhibitions of its prowess" hinted at an Edison-type phonograph doll. Fortunately, an ad on the same day in the rival Globe newspaper provided more definitive detail: "Children's Day at Simpson's Bazaar":

Among various curiosities to be found in this vast collection of holiday goods is a talking doll. A tent has been erected on the second floor of the store and

the children are invited to pay a visit to this particular section, where the talking doll will exhibit her wonderful powers the day throughout. The young lady

in question hails from Paris. She sings about a dozen different songs familiar in children's lore and in a manner that is perfectly astonishing. (14)

No doubt this referred to an exhibition, likely the first in Toronto, of the Bébé Jumeau Phonographe doll which was manufactured by the well-known French doll maker, Emile-Louis Jumeau, with a bisque head and using a tiny clockwork mechanism and removable celluloid cylinder invented

by the highly-respected clock and automaton maker, Henri Lioret. This marvelous device was introduced to the public in an article in the scientific journal, La Nature, on December 9, 1893. The doll was advertised as a talking, singing

doll that recited up to 30 words. Marketed for several years through 1900, the Bébé Jumeau Phonographe doll was more durable than the earlier Edison phonograph doll, encountered fewer mechanical failures and subsequently survived in greater numbers.

It was never mentioned by name in any early Toronto newspaper.

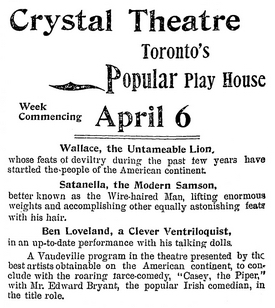

In April, 1896, the Crystal Theatre, Toronto's Popular Play House, advertised "Ben Loveland, a Clever Ventriloquist, in an up-to-date performance with his talking dolls" (15). Here, "talking doll" has been usurped for a completely different purpose and technology - a third, unique connotation of the phrase. Ventriloquism was a sideline for Dr. Ben Loveland who was a member of the Mohawk Indian Medicine Company troop. His June appearance at the Roof Garden at Hanlan's Point with his family of five life-sized wooden-headed figures "was an immediate favourite with the ladies and the little ones, keeping them in continuous roars of laughter". It would be another 21 years before this use of the phrase appeared again in Toronto newspapers when, at the annual banquet of The Globe carrier boys held in the Central Y.M.C.A., the ventriloquist John A. Kelly's "talking dolls insisted in demanding apple pie and ice cream, and the boys enjoyed the fun immensely". (16)

The Evening Star,

Saturday, April 4, 1896, p. 4

|

|

A Robert Simpson Company ad, "Bargain Friday", in both The Evening Star and The Globe newspapers for August 6, 1896, listed "fine talking dolls, 17 1/2 in. in length, 19˘, reg. 30˘". (17)

On September 3, Simpson's offered "a large size Talking Doll, 29˘, regular 45˘" (18)

and on December 5 "Dolls by the Thousands For Christmas" including "Talking Dolls, 60˘ to 75˘". (19)

Two years later, on December 14, 1898, The Harold A. Wilson Co. Limited, 35 King Street West, Toronto, boasted in its new Christmas Catalogue: "Plain Dolls, Dressable Dolls,

Fancy Dress Dolls, Musical Dolls, Talking Dolls, Walking Dolls, Sleeping Dolls, Acrobatic Dolls, Dolls Furniture, Dolls Dishes, Dolls Carriages, Dolls Houses,

Swiss Dolls, French Dolls, German Dolls, American Dolls". (20) Whew!

Finally, on December 28, 1898, a Simpson's ad in The Globe under the heading "Doll Bargains", described "Talking Dolls, natural hands and feet,

says 'Pa' and 'Ma' when you pull the string, our regular 25˘ and 35˘ kind, Thursday 10˘". (21)

In 1902, the Home Specialty Co., 54 Adelaide St. East, advertised a "wonderful speaking doll - laughs, cries and talks, says 'Mamma' and 'Papa' as plainly as any

living child" FREE FREE FREE simply for selling "9 packages of lemon, vanilla and almond flavoring powders" at 10˘ each (22)

or "10 Canadian Home Cook Books" at 15˘ each. (23) This was the first instance in Toronto newspapers of a talking doll being offered as a free premium. It is unclear whether the offer was made

exclusively to dealers, as was likely the Wrigley's doll, or whether it was also available directly to the public.

The Globe, December 13, 1902, p. 4

|

|

The Globe, February 7, 1903, p. 3

|

|

A second free premium, by the Rose Perfume Company in 1903, illustrated a talking doll dressed in a fashion similar to the Wrigley's promotion,

with a "pretty ribbon and fine lace sufficient to make the hat and dress shown in the picture... Dolly has golden curls, blue eyes, pearly teeth, rosy cheeks,

in fact, she is a perfect beauty, and talks, says 'Papa' and 'Mamma' as plainly as you can". (24)

The Globe, December 4, 1909, p. A12

|

|

Ads in 1906 and 1909 offered hundreds of talking dolls including a free premium Peary-Cook North Pole Talking Doll with

a voice like a real Eskimo baby and says 'Mama' and 'Papa' in its own language. This has come to take the place of the squeaking Teddy Bear and is going to be a thousand times more popular.

It is an exact reproduction of the Baby Dolls that the great discoverers, Cook and Peary, saw on their journeys to the North Pole. These dolls are unbreakable. (25)

Two years later the market for talking dolls exploded. In late December 1911 Simpson's offered "Dolls by the Thousand":

1,000 Talking Dolls, say "ma. ma." have full jointed kid body, bisque head and arms, long curly hair, closing eyes, lace hose and fancy slippers, regular $2, Friday

bargain $1.19. (26)

This is an almost perfect description of the Wrigley's doll, which was offered the next year, and it is intriguing to speculate that perhaps Wrigley's purchased its supply from Simpson's or at least from the same job-lot wholesaler.

This brief synopsis has identified three distinct uses of the phrase "talking doll" in early Toronto newspapers to describe three unique types of dolls.

The most common type incorporated a primitive 'voice box' made from a simple reed and bellows mechanism, which elicited a sound, typically an approximation of the word "ma-ma", when the doll was tilted or squeezed or when one pulled a string. The second type,

exemplified by the Edison, Bébé Jumeau and other phonograph dolls, incorporated either a hand-crank mechanism (Edison) or a spring motor (Bébé Jumeau) to play pre-recorded words or music through the medium of a tiny cylinder or disc record.

And the third, least common use of the phrase, described the ventriloquist's dummy, a category of doll that would apply also to hand puppets and marionettes.

In 1919, seven years after the focus of this article, a fourth unique use of the phrase was introduced with the advent of the colourful Talking Book figure records which were produced in Toronto by the Talking Book Company, Limited,

110 Church Street. 4 1/8" discs were laminated to 12" die-cut cards depicting animals, birds and human figures. "The records do not come off the figures. Put the record, figure and all, on any phonograph and play it.

The records will not break". (27) These "talking dolls, animals and birds" were advertised as a combination picture card, story card and real phonograph record - all in one. The experiment was short-lived as the company filed for bankruptcy in 1921.

Talking Book figure records

"Just think of it! This Parrot or Mocking Bird, Lion or Tiger;

Baby, Dancing Girl or Little Hieland Mon goes right on the phonograph

- just as it is - picture, record and all - and gives you a little song,

recitation or imitation of the animals and birds. The newest toy for the

kiddies. They use them as dolls, picture cards, story cards or

Phonograph records. Not only loads of fun, but they educate as well.

They're simply wonderful! And the kids are crazy about them".

The Globe, November 29, 1919, p. 30

|

|

I Am A Dancing Girl

|

|

It would have been exciting to have discovered in the Wrigley's ad a hitherto unknown type of phonograph doll, but it is clear that the Wrigley's doll fits squarely into the middle of a promotional tradition established about 1900

of offering a talking 'ma-ma' doll as a free premium for the sale of a product. This variety of doll ultimately achieved its greatest popularity several decades later in the 1920s and 1930s.

REFERENCES:

- Phonograph Dolls and Toys, Joan & Robin Rolfs, 2004

- Marketing Gum, Making Meanings: Wrigley in North America, 1890-1930, Daniel Robinson, 2004

- In 1909 the Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company rented a small factory at 7 Scott Street in Toronto. This was its first facility

outside the United States. By late 1911 the first batches of Canadian-made Spearmint gum rolled off the assembly lines. In 1914 Wrigley

began construction of a five-storey, 128,000-square foot building on Carlaw Avenue. Completed in 1916, it was patterned in

the Beaux Arts style after the Chicago factory. Wrigley occupied the site until 1963 when, needing room to expand,

the company relocated to a new plant on Leslie Street north of Eglinton Avenue. In 1998 the Carlaw Avenue building was converted

into condominium lofts. In 2016 Wrigley Canada closed down its Canadian factory on Leslie Street and moved its operations

to its USA plant in Gainesville, Georgia.

- "Not Mr. Edison's Talking Machine", Antique Phonograph News, Arthur E. Zimmerman and Betty Minaker Pratt, May-June, 2013

- A Cultural History of the Edison Talking Doll Record, Patrick Feaster, 2015

- Tech Trek: The Evolution of Talking Dolls, Maggie Thrash and Amber Humphrey, 2015

- The Globe, July 26, 1890, p. 10

- Ibid., September 13, 1890, p. 5

- Ibid., March 5, 1892, p. 5

- Ibid., November 12, 1892, p. 2

- The Evening Star, December 15, 1894, p. 2

- Ibid., December 15, 1894, p. 5

- Ibid., December 7, 1895, p. 2

- The Globe, December 7, 1895, p. 21

- The Evening Star, April 4, 1896, p. 4

- The Globe, April 14, 1917, p. 8

- The Evening Star, August 6, 1896, p. 7; The Globe, p. 3

- The Globe, September 3, 1896, p. 3

- Ibid., December 5, 1896, p. 20

- The Evening Star, December 14, 1898, p. 2

- The Globe, December 28, 1898, p. 3

- Ibid., November 8, 1902, p. 3

- Ibid., December 13, 1902, p. 4

- Ibid., February 7, 1903, p. 3

- Ibid., December 4, 1909, p. A12

- Ibid., December 21, 1911, p. 3

- Ibid., November 29, 1919, p. 30

|