|

Curtiss Aeronola and the Post War Effect

by Keith Wright

|

|

Photograph of a Curtiss float

in a 1918 Toronto Victory Bond parade.

(Collection of Bill and Betty Pratt)

|

|

|

As is well known, at the height of the

gramophone production craze during the

late teens and the twenties of the twentieth

century, talking machines were being produced

by a plethora of companies in Canada. Some

had definite bona fides to do so, such as Casavant

Frères of Quebec, who produced world-class

pipe organs, and the various piano manufacturers

such as The Amherst Piano Factory of Nova

Scotia and Gerhard Heintzman Ltd. and Mason

& Risch of Toronto. Others had somewhat

tangential expertise, such as the Brantford Piano

Case Company and George McLagan Furniture

Co. Ltd. And then there was the seeming-outlier

among the bunch, Curtiss Aeroplanes and Motors

Ltd. During my research into W.H. Banfield and

Sons, who were machinists and went into the

production of ‘phonograph motors’ and perhaps

whole machines, it dawned on me why Curtiss

would have made such a curious change in

production.

Announced in The Toronto Daily Star on February

12, 1915 was that an aeroplane factory was to be

located in Toronto. “150 Men To Be Employed to

Build Biplanes for Military Purposes,” and

“Pilot to Be Trained Here for the Canadian Contingent

of British Army.”

As noted

“Mr. J.A.D.

McCurdy…has formed a company which will be

in operation almost at once to manufacture these

machines. Mr. McCurdy has been in close touch

with Glen Curtiss…one of the most prominent of

aeroplane builders in the States, and the machines

which will be constructed will be of the standard

Curtiss types…”

And later in the article,

“Along with construction, arrangements will be made

to train pilots to handle the machines…”

|

|

|

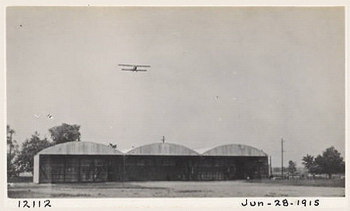

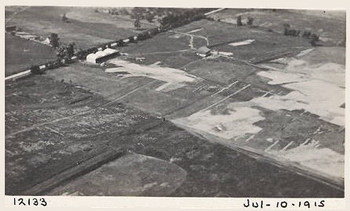

Long Branch Aviation School started by Curtiss company, 1915.

(Images courtesy John Boyd Sr. Toronto military training photograph

album from the Toronto Public Archives)

|

|

|

On February 22 the same year, it was reported that

the company received an order for 8 planes from

the Dominion Government. Things continued to

go well for Curtiss/McCurdy as a report later that

same year noted that there was “Money In Aeros”

with the Curtiss company receiving $15,000,000

from Great Britain after having already produced

$6,000,000 worth of aeroplanes and motors in the

previous fiscal year, most of which went to the

British Government. (Another report mentioned

that representatives of the Spanish Government

were buying Toronto-made planes.)

The flying school was located in Long Branch

where the old Lakeview generating station (of the

“four sisters” chimneys fame) later resided and

was, in fact, the very first airport (“aerodrome” at

the time) built in Canada. The school itself was

reported to be the “largest in existence”.

|

|

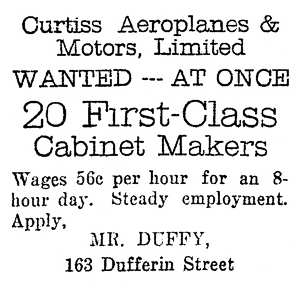

Curtiss looking for help to build the many

gramophones they were

planning.

(Toronto Daily Star, August 9, 1919 pg 18)

|

|

|

This article is not intended as a review of

Canadian aviation history, but as background.

John Alexander Douglas McCurdy (August 2,

1886 – June 25, 1961) was born in Baddeck,

Nova Scotia and graduated from the University

of Toronto in mechanical engineering and

became the first Canadian to receive a pilot’s

license. In 1907 he joined the Aerial Experiment

Association (AEA), along with another U of T

graduate, Frederick W. “Casey” Baldwin, under

the leadership of Alexander Graham Bell—

who not coincidentally had his summer home

in Baddeck, Nova Scotia and whose one-time

personal secretary was McCurdy’s father. Later

the group recruited Glenn Curtiss, a bicycle

racer who developed an interest in motorcycles

and went into their manufacture. At one time

Curtiss was known as the “fastest man in the

world” after setting an unofficial speed record

on a motorcycle—which went unbroken for 23

years. The AEA experimented with heavier-thanair

machines in Hammondsport, New York and

Baddeck, Nova Scotia. Curtiss would later found

an aeroplane company in the US, which in part

still exists today as Curtiss-Wright.

As noted above, the Curtiss plant in Toronto

was created to manufacture training aircraft for

the British Government. However, according

to the Canadian Aviation Museum,

“Within days of the training program’s approval, on

December 15, 1916, Canadian Aeroplanes was

incorporated for the purpose of providing all

aircraft required by the training schools. The

Canadian-based Imperial Munitions Board,

an organization responsible for awarding war

contracts to Canadian manufacturers, took over a

small airplane manufacturing plant in downtown

Toronto, formerly used by Curtiss Aeroplane &

Motor Limited [possibly the 163 Dufferin Street

location]. But the expanding company soon

outgrew this space and, by May of the following

year, all operations had been moved to a new

plant (still in Toronto).”

It was 1244 Dufferin Street which includes the land

where the Galleria sits today.

As I mentioned before, it was research into W.H.

Banfield and Sons that drew my attention to the

idea of post-war production. Obviously as WWI

ended, the amount of manufacturing capacity for

war material, including human resources, wasn’t

required and the populace could concentrate

on more domestic matters.

|

|

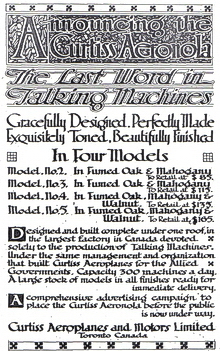

(Canadian Music Trades Journal,

Volume 20,

No. 2, July 1919)

|

|

|

|

(Edmonton Journal,

September 27, 1919, pg. 19)

|

|

|

|

(Toronto Daily Star,

December 22, 1919, pg. 22)

|

|

|

The major patents

protecting the North American talking machine

triumvirate (Edison, Victor and Columbia) were

expiring and thus the talking machine boom

began. There is a full page in the November

29, 1919 edition of The Globe devoted to

talking machines, pianos and the music industry

in general. On that page there is an article

about how, with Columbia taking over the 11

buildings of Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd. (1244

Dufferin—not the original site of Curtiss)

“there is the assurance of a considerable expansion

of talking-machine manufacture in Canada …

[which] will increase Canadian output from

400 to 500 percent.”

There is an article about

W.H. Banfield and Sons applying the

“war’s big production

lessons…to peace-time business…

The munitions plant…is now working at top

speed on phonograph motors—and phonographs.”

|

|

ID plate from an electric 78 player for sale in 2015.

(Image courtesy of the author)

|

|

|

There is also an article about how a “Stratford

Firm [McLagan] is Forging Ahead, Putting

Phonographs of Wide Variety on the Canadian

Market.” And then, there is an article noting,

“Aeroplane Company Making Phonographs.”

“’We challenge the statement that there is a

dearth of musical education and appreciation in

Canada,’” said Mr. E. Sterling Dean, who is in

charge of advertising for the Curtiss Aeroplanes

and Motors, Limited, which has begun recently

the manufacture of talking machines.” Dean

continues to suggest that “any boy or girl living in

the average home [ can name] the most prominent

violinists of the day or the most famous singers”

to which he “ascribes…the perfecting of the

talking machine, which is within the means

of many more persons than the piano.” The

article continues to claim that Curtiss “which

had been making airplanes for the allies, finding

their factory ideal for the purpose, turned to the

manufacture of talking machines. They obtained

well-known talking-machine experts to assist…

Mr. Dean says that the models…reveal startling

accuracy.”

What else would he say?

|

|

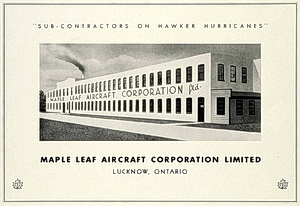

Image purported to be of the Maple Leaf

Aircraft Corporation

around 1942.

(From an eBay listing, March 2015)

|

|

|

There are employment-wanted adverts in the

Daily Star (August, 1919) and The Globe

(October, 1919) for cabinet makers and others,

for the 163 Dufferin address, who would be

more suited to talking-machine manufacture

than aeroplanes. I do note that they are looking

for finishers as the only motors that have been

mentioned are all from the Newark N.J. thirdparty

MeisselBach—whose motors turn up in

many “off brand” machines. Curtiss must have

had high hopes as an issue of Canadian Music

Trades Journal (October, 1919) claims that

“12,515,000 Advertisements will appear in Press

between now and Christmas.” It sure looks like

there were that many. Then…not so much. I

have found no references to them so far after

1919, until they are included in the “fire sales” of

1929—presumably as used or left-over stock. If

the public didn’t initially take to them, there is a

small cadre of collectors today who have.

Of all the people who have contributed to the

40+ talking-machine brands in the Canadian

Antique Phonograph Project, the Aeronola pilots

are different. They have done more research on

their own than any others and there is a palpable

pride in how they have carefully made sure that

the page lists each of the six known existing

machines with as much detail as possible.

According to Aeronola-owner Carl Swanston,

the company was forced into receivership in

1920 and the facility became the General (car)

Top Company in August of 1920.

“The Curtiss

Company was then managed by Canadian

financier Clement Keys who brought it back to

prosperity sans gramophone production.”

|

|

Electric 78 attachment ostensibly from the Maple Leaf Aircraft

Corporation of Lucknow, Ontario.

(Image courtesy the author)

|

|

|

Finally, I take this opportunity to mention a

later example of the post-war production effect.

In February of 2015 a curious electric 78 rpm

turntable, clearly from the 1940s, showed up at

a meeting of the Canadian Antique Phonograph

Society. It was a typical, lidded attachmentturntable

but on the underside it had a plate that

in part read, “Maple Leaf Aircraft Corp. Ltd.

Lucknow Canada”.

According to the “Furniture Factories Information

Sheet” of the Bruce County Museum and Cultural

Centre,

“In 1898, John Button and H.J. Trevett,

known as Teeswater Furniture Company, moved

their machinery to Lucknow. They specialized in

tables. A modern, fire-proof, concrete building

was completed in 1907. During World War II, the

firm made [war] products under the name Maple

Leaf Aircraft. Following the [war], William

Renaud operated the furniture factory for a short

time.”

In an article about local Lucknow war hero

Warren Wylds, writer Garit Reid notes,

“Before entering the military Wylds worked as a foreman

at the Maple Leaf Aircraft in Lucknow where he

supervised a crew that made hydraulic systems for

landing wheels for military airplanes; one of the

many things made for the military at Maple Leaf.”

I have also found a picture of what is purported

to be the Maple Leaf factory in Lucknow circa

1942 that is labelled, “Sub-contractors on Hawker

Hurricanes.”

No more is known at present about the 78

attachment from Lucknow but it certainly looks

like another example of what would much later be

called the “peace dividend”.

References

|

|

Aeronola phonograph in the collection of Carl Swanston.

Serial number 5M620, motor number 170523.

|

|

|

- John Boyd Sr. Toronto military training

photograph album, Toronto Public Archives,

Fonds 1548, Series 1418, File 1, Item 31.

- Canada's First Aerodrome, Long Branch

Curtiss Aviation School by Liwen Chen for Heritage Mississauga.

- Toronto Daily Star, May 19, 1908, pg. 3.

- Ibid, March 1, 1909, pg. 2.

- Ibid, July 22, 1909, pg. 3.

- Ibid, August 9, 1919 pg 18.

- Ibid, February 12, 1915, pg 12.

- Ibid, February 22, 1915, pg. 5.

- Ibid, December 15, 1915, pg. 2.

- Ibid, July 14, 1915, pg. 4.

- Ibid, July 15, 1915, pg. 1.

- Ibid, August 9, 1919, pg. 18.

- Ibid, December 22, 1919, pg. 22.

- Ibid, March 27, 1929, pg.2.

- Edmonton Journal, September 27, 1919,

pg. 19.

- The Globe, November 29, 1919, pg 23.

- Canadian Music Trades Journal, Vol. 20,

No. 5, October, 1919, pg. 42.

- Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd. "mini exhibit"

from the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum

- Curtiss Aeronola page from the Canadian Antique Phonograph Project

- Aviation in Canada: The Pioneer Decades, Larry Milberry, CANAV Books, Toronto, 2008.

- Furniture Factories Information Sheet of

the Bruce County Museum and Cultural Centre.

- The Homefront during WWII was just as

important by Garit Reid, Lucknow Sentinel,

Nov. 11, 2009.

- Carl Swanston, personal correspondence with

KW.

|