|

How My Train Jumped All 8 Tracks or Elvis Cool To Truck Stop Cruel

Program 2

by Keith Wright

Intro

|

|

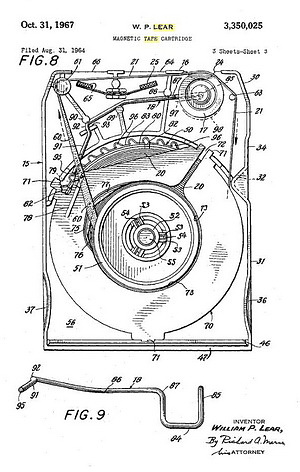

This drawing is from the series of patents filed in 1964. Note a main difference from the 4-track—the pinch roller is inside the cart.

|

|

|

Will: "This is either madness, or brilliance."

Jack: "It's remarkable how often those two traits coincide."

(Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl)

The story so far: the work in magnetic recording started by Oberlin Smith and given form by Valdemar Poulsen in the late 1800s eventually leads

us to George Eash's "Fidelipac" ("3 tracks", with left and right channels and a cue track) of the 1950s. This self-contained infinite loop of

magnetic tape was used in radio into the 1990s and also turned into a system to play pre-recorded music by the TV entrepreneur and "master used

car salesman of all time", Earl "Madman" Muntz. The 4-track "Stereo Pak" (2 programs of 2-channel stereo), despite Muntz, almost becomes "the first

widely successful consumer tape format". Unfortunately for the Madman, someone gets taken for a ride.

Now, once again lean back, push the cart into the machine and give free reign to that sound in your head. The cart has reached the sensing-foil

to change programs. Here we go to program 2. Let it happen. No one will know...

[**Ka-chunk**]

Program 2 - Big Bang or Madman and Jet #2

[sound fades in]...If I said that someone was a high school drop-out, had a daughter with an 'unusual' name, built a jet, married multiple times,

built a radio when he was young, and put tape players in cars, who would you think I meant? In my last article, I said all of these things about

the remarkable [ahem] Madman Muntz but they also count equally true for William Powell Lear.

Lear Jet is stamped on the back of many an 8-track cart, but it comes as a surprise to some that the aviation maverick and ‘celebrated' genius had

anything to do with the endless loop. However, I did mention two things about him last time: Lear was associated with a wire recorder in the 1940s

and he later became a distributor for the Muntz Stereo Pak. When I did a rewind, it was quite easy to see how everything fell into place. As

we go through the second part of our story, keep these things in mind: planes may have been Lear's passion (and he sure gave free reign to his

passions) but electronics was his original profession; he did early work in car radio; he was asked to build a wire recorder; and he couldn't stop

himself from improving on the work of others. It was fate.

In Grant Park on the Chicago lakefront of 1919 "Willy" Lear was 17 when he encountered the "flaming coffins"—the DH-4 airplanes—of the US Aerial Mail

Service. He was a high school drop-out ("couldn't learn airplane mechanics there") who had quit his job monitoring electric generators to volunteer

as a grease monkey, getting the occasional ride in a mail plane. The planes he encountered had no gyro compasses to keep them on course, no "turn and bank"

and no radios. He would later vastly improve the instruments available to pilots. By the time he was 12 he had already built a radio set with earphones,

mastered Morse code and pieced together a crude telegraph, including storage batteries made out of old Mason jars.

By 1922 he had studied radio in the Navy and, after his discharge, talked his way into a job as a radio salesman while starting his own basement radio

workshop and school. It was hard to sell a radio to someone who hadn't heard one before. During one radio demo, one customer said, "That's a wonderful

song. Play it again." In those days people bought radio parts, used store expertise and built their own sets. But shortly thereafter, the "Harmony"

do-it-yourself kits came out and all but killed Lear's business. He had made some innovations but didn't file for a single patent. It was also during

this time that he began experimenting with car radio. There were big problems for radios in the "noisy" electrical environment of the automobile and

5 years later this experience would bring him fame and fortune.

You might say Bill had more than his share of confidence. When a friend asked for advice on getting a date with Madeline Murphey, Bill instead said,

"I'll bet you a dollar I can get a date from her before you can." Not only did he win the bet, he eventually made her wife #2. However, before divorcing

wife #1, he was on the run with Madeline and was arrested by the FBI, who had been sent by Madeline's sister (transporting the young woman triggered the Mann Act).

At 24 years of age Bill Lear was bankrupt. He had rebuilt a radio station for his grandmother's church, built a plane that didn't fly (the first plane built in Tulsa),

married twice and been indicted for a federal crime (transporting Madeline inter-state). It was then that he went back to Chicago, the largest radio manufacturing

centre in the country, to start over. He was to get his first big break there.

June 13, 1927 was to see the first radio manufacturers show open at the Chicago Stevens Hotel. Approximately 8,700 manufacturers, jobbers, dealers and

advertising execs from all over the country were there to display their new 1928 models—including all sorts of new alternating current (AC) equipment.

But the organizers had neglected one thing—the Stevens Hotel had its own DC generators and none of the new AC equipment would work. At the last minute

new generators to convert DC to AC were built but Lear had learned from his work on car radio and he bet that the electrical "noise" would wreak havoc on

the radios. He waited until panic set in, then he confidently announced he could solve the problem for $1000. "By the time the convention opened there

was hardly a manufacturer's representative who hadn't heard of Bill Lear" (said Richard Rashke). Lear worked 100 hours around the clock and built a

series of filters for every piece of electrical equipment on display. The experience would be invaluable.

October 29, 1929, crushed 253 of 258 companies building radios in the US. But Lear continued to thrive, selling coils, troubleshooting, and doing electronic

design. One customer was Galvin Manufacturing Company. It was in that climate that Lear suggested to owner Paul Galvin that they make car radios. Mounting

radio controls on the steering column was Lear's first patent and they came up with the name "Motorola", from "motor Victrola". In the second half of 1930, Galvin

Manufacturing made and distributed almost 1000 Motorolas and eventually Galvin would rename his own company to the brand of this popular product.

I must interject one editorial note here. Even Lear's biographer, Richard Rashke, warns of "Lear hype". Stories told of and by Lear easily morph into fishing

stories (it was that big....no THAT big) so I was careful after hearing that Lear had "invented the car radio". Motorola makes no mention of Lear in its own

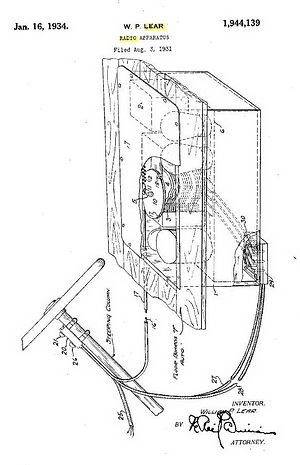

telling of the story, but you can see for yourself that William P. Lear is on the 1934 patent (filed in1931, Fig. 1). (One example of Lear hype: Lear's

claims of selling a "quarter of a million dollars…" and leaving Chicago because he was "in a rut" in truth turned out to be less than $100,000 and leaving

to escape financial disaster.)

With his new found financial comfort, Lear bought a plane and learned first-hand the perils of "modern flight". As noted, he had already learned about a

similar environment to the plane for electronics (the auto) and at this time he also lost interest in the radio business. As Raymond Yoder puts it, "Bill

was like that. He'd get an idea, talk it over with you. You'd agree to give it a try. He'd get you going on it, then lose interest." He was also known to

have only one speed, 100% forward, once famously yelling at an engineer, "One more degree and you'd be a f-ing idiot!"

|

|

Drawing from Lear’s (and Galvin’s) 1931 patent application for the car radio.

|

|

|

Lear left the safe, profitable radio business and started all over again in navigation instruments. This article is not about Lear's mainstream success,

so we can summarize by saying that he developed a series of electronics for planes that would eventually win him the Collier Trophy—the "Pulitzer Prize

of aeronautics". But within this period a number of things pointed toward our story of the endless loop:

| •

|

During WWII, the US Signal Corps recovered a wire voice recorder from the cockpit of a German reconnaissance plane and asked

Lear to study the machine and to build one for the US. This work likely later produced the ‘Learecorder'.

|

| •

|

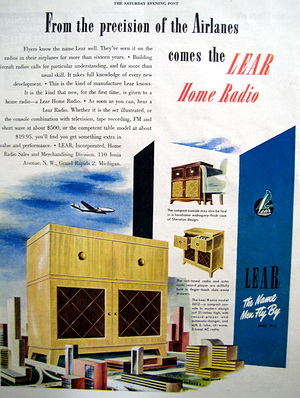

He created a $600 radio-phonograph and couldn't compete with the $23 plastic radios of the time.

|

| •

|

In 1948 the Learecorder was announced as "the most versatile home musical reproduction machine ever built"

(New York Times). But it had a troublesome problem where the wire snarled and broke. While this problem was being fixed, magnetic tape took over the market.

|

| •

|

Lear developed the "Learpeater tape", which stores could use to announce their bargains to shoppers over and over

(shades of Cousino's "Audovendor"?). However, the board of directors of his company blocked production as there was no production money.

|

| •

|

Lear started to develop a corporate jet from a Swiss design dubbed the "Swiss submarine" (2 pilots had ditched their planes

into Lake Constance and the Swiss thought Bill, "absolutely out of his mind" to consider it). As Time put it: "Lear severed connections in 1962 with

the electronics firm he had founded, anted up $11 million of his personal fortune, squeezed bank loans and tapped his children's trust funds to finance

production of the small, streamlined, low-cost jet now used by corporation presidents and rock stars alike."

|

It was also in this period that Bill married Moya Olsen (his 4th and final wife), who was the daughter of Ole Olson of the Broadway hit, Hellzapoppin' fame.

This is pertinent as one of the children of this union was Shanda. Shanda Lear. Get it? "After the kindergarten teasing over my name, no challenge seemed

insurmountable," joked Shanda, who is currently president and CEO of the Lear Baylor Electric Boat company—and also the "canary" for several swing bands

in the LA/Orange County area...

By 1954, "William Lear, [had] …built his Lear, Inc. into a $50 million company making automatic pilots and other electronic gadgets, [and become a

millionaire by taking] capital gains by selling off inventions." ("New Millionaires", Time Dec. 27, 1954)

In "Flight to Russia", Time (July 9, 1956) reported, "For nearly six months, peak-nosed Airman William P. (for Powell) Lear, 54, a restless,

uninhibited manufacturer-inventor (Lear, Inc.), has been flying his Cessna 310 plane around Europe on a businessman's crusade. He wanted to

show Europeans how simple and safe it was to fly their own planes, especially with the Lear automatic pilot, the Lear automatic direction

finder and the Lear omnirange navigational system. Fortnight ago, in Hamburg, Bill Lear got an even better idea. Why not be the first postwar

private flyer to go to Moscow and show off U.S. equipment?" And he did. "Then came the explosion. The U.S. embassy in Moscow ordered Lear to explain

what he was doing there, said that all his automatic flight equipment was banned under NATO embargo from sale to the Reds."

We finally get to the quintessential event of the 8-track story. This is the version told by Richard Rashke in Stormy Genius, The Life of Aviation's

Maverick Bill Lear (1985):

"Early in 1963, before the Lear Jet made its first flight, Shanda picked up her father [in a car] she had borrowed from the son of Earl Muntz...

Attached to the dashboard was Muntz's new four-track car stereo player. Shanda knew her father would be interested in the [player] because of his

early work on car radios and wire recorders.

"Not only was he interested, he immediately sensed a great market potential…Lear asked Shanda to drive him to see Muntz. When he left...a few hours

later, Lear was sole Midwest distributor for the Muntz Auto-Stereo. And when Lear landed...in Wichita, [his plane] was filled with Muntz add-on tape players.

"Lear and his chief electronics engineer, Sam Auld, began tearing the players apart to see how they worked."

Auld later said, "A lot of times, just the two of us would be there until maybe two o'clock in the morning. Some nights we were there all night.

And a lot of times, when we needed a part modified, Bill would actually go back into the machine shop and take the part with him and chuck it out on the lathe."

Initially Lear and Auld tried to make improvements, but eventually they came to the conclusion that they would, "start from scratch and make one the way it

ought to be." Their plans were: to make a player with a better steady-speed motor; to make the cart less complicated and prevent snarling like Lear's old

wire recorder; and to increase the amount of music on the cart from one hour to two.

For the last improvement, there were two options: slow the tape speed to 1 ¾ ips from 3 ¾ (but tape at that time wasn't good enough) or increase the number

of tracks from 4 to 8. Lear approached Alexander M. Poniatoff of Ampex who said you couldn't squeeze that much information onto the tape. The bull in

Lear immediately charged that red flag.

|

|

Playtape player and tapes for sale at an outdoor show, 2007.

Short-lived continuous-loop competitor to 8- and 4-track.

(Photo by Keith Wright)

|

|

|

According to the History Department at the University of San Diego: "In 1963 Lear had

become a distributor for Muntz and put the 4-track Fidelipac in his jet. He worked on the 8-track device in 1964, ordering small heads from Nortronics

of Michigan. His cartridge was the same size as the Fidelipac and used the same double-coated tape. The crucial difference was the new heads from

Nortronic. He made 100 Learjet Stereo-Eight players in 1964 for executives of RCA and the auto companies. Ford agreed to install the player in its

1966 models as an option (helped by Lear's ties with Motorola, which was the electronics supplier for Ford). RCA agreed to release 175 recordings in 8-track.

By 1967, 2.4 million players were sold, and the 8-track player became the first tape format to succeed in the mass market."

<< http://history.sandiego.edu/GEN/recording/lear.html>>

As Auld said, "With Lear Jet going on and the eight-track, Bill was in seventh heaven."

From "Carnegie Hall on Wheels" (Time April 30, 1965): "The executives of the Ford Motor Co. have been driving around Detroit lately with an unusually

rhapsodic look on their faces. The look is not the result of Ford's soaring sales—which were up 23% for the first quarter—but of a new auto accessory

that Ford hopes will increase its sales even more. Board Chairman Henry Ford II has one in his Lincoln Continental; Vice President Lee Iacocca has one

in his red Mustang. Using one on the way home makes Ford Division General Manager Donald Frey feel that he is ‘sitting in the middle of Carnegie Hall.'

The device, which Ford this week announced will be offered in most of its 1966 models: a dashboard stereotape player that will permit motorists to hear

their favorite music on an 80-min.-per-tape cartridge —without interference from bumpy roads, tunnels, bridges or commercials. Price: about $150.

"The new stereotape player is also music to the ears of the recording, stereotape and electronics industries. The sales of stereotape cartridges—which

can be easily inserted, eliminate threading and rewinding of tape—have been disappointingly low since their introduction several years ago, largely

because of the lack of a standard cartridge

size and speed. [?] Ford expects to sell 100,000 dashboard stereotape players the first year, but that is just the beginning of a whole new market:

other automakers are sure to join the race, and potential sales are estimated at about a million dashboard units a year.

"The lure of this high volume has brought several major companies into the stereotape market, is increasing pressure for standardization. RCA Victor,

which will record tapes for Ford, has selected a cartridge system developed by Wichita's Lear Jet Corp., recently demonstrated it in Manhattan to 40

other recording companies in a pitch for adoption of an industry standard. On the strength of Ford orders, Lear has set up a separate division in

Detroit to manufacture its tapes and cartridges. Motorola, which is building the dashboard players for Ford, is already working on the next stage

of cartridge stereo-tape development: a home model that will play auto tapes. For its part, Ford will stimulate sales by selling stereotape cartridges

in its dealer showrooms, featuring RCA recording artists in its ads. Perhaps the company will even send owners of stereo-equipped Ford cars occasional

free cartridges of taped music, interrupted here and there by a message from the sponsor."

Motorola produced the new players under license to Lear. By the way, that comment about lack of tape standards is puzzling. The Phillips compact cassette

was not a factor at this point so the only other cartridge to rival the 4- and 8-tracks was the Playtape—but that was only a portable player at this time.

"In a Merry Stereomobile" (Time, August 5, 1966): "Destination: office. Driving time: Beethoven's Third Symphony, Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto, and,

depending on traffic, two or three numbers by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. Driver squiggles into bucket seat, straps on safety belt, injects stereotape

cartridge into dashboard holder, and, to the engulfing strains of the 100-piece Boston Symphony, rolls away on wheels of song.

"So it is in today's all-purpose stereo-mobiles.

Thanks to its introduction into cars, the stereotape cartridge has become the most significant innovation in the $830 million-a-year record market

since the advent of the LP in 1948. Four-track stereotape players for autos, sold mostly on the West Coast, have been available for about five years.

Not until last September, when the Ford Motor Co. began offering a new eight-track player and cartridge—which crams up to 80 minutes of music on half

the length of tape used in a four-track cartridge—did stereotapes begin booming. Lear Jet Corp. and RCA Victor developed the new cartridge and player.

The eight-track sets sold so well (250,000 to date) that Chrysler recently introduced its own set, and General Motors and American Motors will follow

with their units beginning with ‘67-model cars. Manufacturers expect to sell 630,000 eight-track sets this year, 1,500,000 next year."

A quick aside from Andrew D. Crews' December 1, 2003, article from Introduction to Audio Preservation and Reformatting: "Another 1960s cartridge

format was the Playtape, introduced into the market in 1966 by Frank Stanton. Like the 4-track and 8-track, the Playtape was an endless loop format,

but with only two tracks. Stanton developed the format, not for use as a car stereo, but as an affordable replacement for a transistor radio.

Playtapes were produced for use in portable players marketed by Sears and MGM…

"…Once the 8-track and 4-track formats moved from car to personal stereos, the Playtape was doomed. [The other two formats] offered higher fidelity

equipment and greater versatility with the car stereo option. Volkswagen dealerships offered a Playtape car stereo as a dealer option in 1968, but

it was too late. After 1971, the Playtape format disappeared from the market."

|

|

Advert for Lear's home radio (and $500 all-inclusive console).

Saturday Evening Post, May 25, 1946.

(Collection of Keith Wright)

|

|

|

According to Lynn Fuller, "Playtape was touted as a replacement to the transistor radio with the disc jockey removed. It was a light little machine,

playing whatever music you wanted to hear. The self-winding tapes played from eight to 24 minutes, and they played anywhere. Quite an accomplishment

in 1967!" (PlayTape—The 2-Track Alternative, 8-Track Heaven )

So the 8-track was cheaper to produce as the carts were less complex, it contained more music, and it had the impetus of being offered on your new car

instead of being an aftermarket add-on. The Muntz Stereo-Pak would hang on for a few more years. I have not been able to confirm this, but a fire at

the manufacturing plant may have helped its demise. Further proof is required to confirm that this fire wasn't earlier and with another Muntz product (TV).

But back to Lear, who had quite the ride with the Lear Jet, 8-track and other corporate activities. A fast-hitting airplane sales slowdown in late

1966 hit Lear hard (some pundits incorrectly thought it was an on-coming recession). He couldn't ride it out because of too much overall expansion: developing

another model of jet; buying and expanding a helicopter company; plant expansion; and development of the 8-track. Stock that was $82.50 in 1965 was $8.50

in 1966. Lear sold out at $11.89 to Gates Rubber Co., in April 1967 and Gates Learjet would sell more planes than Bill Lear ever predicted while the Stereo-Eight

would become a steady profit maker.

Lear at 65 was a multi-millionaire who didn't know what to do with himself. By turns he was suicidal, was ill, explored for uranium, drilled for oil,

and looked through Alaskan goldmines. Eventually he cottoned onto replacing the internal combustion engine with space-age steam technology.

"I want to be the man who eradicated air pollution," he once declared and while he was working on it, "I've never had so much fun with my clothes on."

(from "A Doctored Stanley, We Presume?", Time, April 11, 1969). "…according to Lear, "[it] can burn anything from ground camel dung to high-grade

gasoline"—although he recommends kerosene."

"On his deathbed, Lear asked his wife Moya, now 65, and Company President Samuel Auld, 55, to use the proceeds from his estimated $100 million

estate to complete work on [a new airplane] the Lear Fan 2100" (from "Queen Lear", Time, July 7, 1980).

From Time May 29, 1978: "DIED. William Lear, 75, restlessly creative inventor whose farsighted triumphs include the first practical car radio,

the autopilot for airplanes, the eight-track stereo cartridge and, more recently, the Learjet; of leukemia; in Reno. Throughout a prodigious career

that eventually netted him more than 150 patents, Lear delighted in tackling ‘impossible' problems." Learjet is now a subsidiary of Bombardier Aerospace.

It was the 8-track boom—which actually has an alternate story as an origin. But I'm getting ahead of myself again.

I don't think I made enough of a point about Bill's passion. Besides his 4 wives, he apparently had quite the number of…er…"friends". Nils Eklund

said that when Lear was flying the autopilot coast-to-coast he prepared his trip meticulously. "Bill had a girl in each town. After working all night,

he'd call them all over the country. Each one was like she was the only one. Whenever we came into an airport, there would be a woman in the limousine to pick us up."

According to Fortune (July 1965): "During the 1930s and 1940s [Lear] was a part-time and enthusiastic participant in New York's night life, and his table

at the Stork Club (which he called "my night office") became the after-theatre rendezvous for show people, mostly female."

Then there was "The General"—the code name for a "secretary" who was paid $600 a month and never showed up for work. Lear's son-in-law was brought in to

help turn the company around and promptly fired her. But then some one in the company "explained" the "facts" to him and "The General" was reinstated...[sound fades out]

Keith Wright is editor of APN. [nudge, nudge, wink, wink]

|