|

Donalda: A Canadian Melba?

by Keith Wright

|

|

Pauline Donalda nee Lightstone or Lichtenstein.

Canadian opera singer whose career spanned 1905 to 1922.

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

|

|

|

As is often cited, the major equipment

patents on phonographs, gramophones

and talking machines began to expire

near the end of WWI. This enabled others—

previously too timid to jump into production,

unlike Pollock of Berlin, Ontario— to enter

the business and compete with Victor/Berliner,

Columbia and Edison. In those days, when

mass transport of goods was not cheap or

convenient, local manufacturers with tangential

expertise sprang up to supply their neighbours,

and perhaps beyond, with machines of various

quality. Thus begat the bewildering number

of companies that are currently listed by the

Canadian Antique Phonograph Project (accessible

directly CAPP or

through the CAPS main page CAPS).

Naturally, we would expect

these companies to be distributed according to

population density, which begins to explain a lack

of representation from provinces west of Ontario.

Until recently.

As is so often the case, this story begins with an

e-mail:

“My mother bought a cabinet gramophone,

around 50 years ago, from a Salvation Army Store

in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It stands on legs, has

storage for records on the left side and a drawer

on the bottom. It is marked with the Hudson Bay

Company Logo on the inside, and also a Donalda

logo as well.

“[signed] Lynn Houde”

Pictures later supplied show a typical console

model with the described Hudson’s Bay Company

and “Donalda” logos. I can’t remember the

precise, “aha” moment but my research started in

two places and fortunately met in the middle.

Pauline Lightstone was born in Montreal in 1882

of Russian and Polish parents who changed

their name from Lichtenstein. She studied music

on a scholarship at the Royal Victoria College.

Her father sought confirmation of her talents,

which was received from French tenor Thomas

Salignac, and allowed her to study opera in Paris

starting in 1902, on a grant from one Donald

Smith, Lord Strathcona. Pauline made her debut

in 1904 at Nice, apparently with the help of

French composer Jules Massenet, and allegedly

|

|

Detail of console “Donalda” model that sparked the research.

Image courtesy Lynn Houde.

|

|

|

to honour her benefactor adopted the stage name

Pauline Donalda (aha?). She made her London

debut at Covent Garden in 1905, her professional

Canadian debut in 1906 and her New York debut

later the same year (after breaking her contract

to accept an offer from Oscar Hammerstein’s

Manhattan Opera Company). The Canadian

Encyclopedia entry makes the rather prescient

comment, “[Donalda was] Considered a rival of

[famous Australian operatic soprano Dame Nellie]

Melba, she often replaced her and thus sang Mimi

with Enrico Caruso.” (An interesting side note

is that Lord Strathcona earlier brought one Clara

Lichtenstein to Canada (no relation), who became

director of music at the Royal Victoria College

and had a profound and lasting effect on Pauline.)

Pauline’s performing career spanned 1905 to

1922, including nine recordings, after which

she turned to teaching and administration. She

opened a studio in Paris in 1922 where she taught

before returning to Montreal in 1937 where she

again opened a studio, then in 1942 founded the

Opera Guild. In 1967 she was made an Officer

of the Order Of Canada and died 3 years later in

Montreal. On the recording side, she cut 7 sides

for G&T in London, 1907 and 1908, one for

Victor in 1914 and one for Emerson around 1916.

|

|

Donald Alexander Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal

ceremoniously driving the last spike of the CPR November 7, 1885.

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

|

|

|

Starting from the metaphorical other side of the

river, The Right Honourable Donald Alexander

Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal,

cuts an impressive swath in Canadian history.

He was president of the Bank of Montreal, co-

founder of the Canadian Pacific Railway (he

is in the famous photograph driving the last

spike at the railway’s completion), chairman of

Burmah Oil and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company,

high commissioner for Canada in the UK, and

Chancellor of McGill University and Aberdeen

University. Elected to the provincial legislature

in Manitoba’s first general election, he was also

elected to the House of Commons. For our story,

however, we need only to concern ourselves with

two slivers from this massive biography. King

Edward VII is said to have called him “Uncle

Donald” in reference to his philanthropy, which

apparently totaled over $7 million during his

lifetime. Clearly a sprinkling made it in Pauline’s

direction. The other sliver is the fact that upon

his original emigration to Canada in 1838, as

the nephew of a fur trader with the North West

Company and former HBC Chief Factor, he

started working for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

He rose through the ranks over a 75-year career

becoming at one point the company’s largest

shareholder and in 1889 being named their 26th

Governor (aha?), a post he would keep until his

death at age 93. He was given a state funeral in

Westminster Abbey, in 1914.

|

|

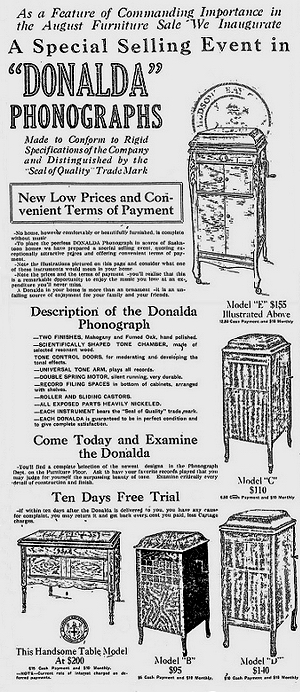

“Donalda” phonograph line, Saskatoon Phoenix, August 11, 1922, pg. 12.

|

|

|

So, my current theory is that a series of

gramophones was made to be sold through

the retail arm of the Hudson’s Bay Company

under the name “Donalda”, likely in honour of

the famous Canadian opera singer, who retired

from singing about the time the machines were

available. I wonder if they were at all aware that

they were also honouring one of the most famous

managers of the company?

Naming a gramophone after a famous opera star

does have a precedent.

The Compleat Talking

Machine: A Collector’s Guide to Antique

Phonographs

by Eric L. Reiss has a picture

on the rear cover of the author with an ornate

outside-horn machine labelled a “Melba”.

The accompanying text reads, “The ‘Melba’

gramophone was produced by the Gramophone &

Typewriter Co. in England around 1904. Named

for the famous opera singer, Nellie Melba, with its

12” turntable, triple-spring motor, and elaborate

‘art nouveau’ cabinet, the Melba was G&T’s top-

of-the-line model. Quite rare today, surviving

Melbas are usually found with brass horns...”

Dame Nellie Melba of course became one of the

most famous opera singers spanning the late 19th

and early 20th centuries.

In researching the “Donalda” machines

themselves, we find a narrow window of Hudson

Bay Company adverts in western newspapers

during 1922 and 1923. One 1922 advert shows a

handful of uprights in the $95-$155 range as well

as one $200 console—which does not quite match

the machine from the e-mail that started the story.

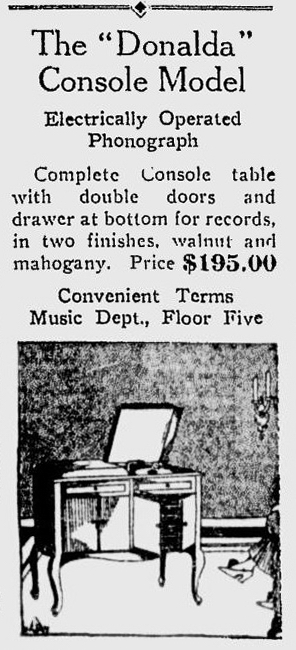

Of more interest is a later 1922 advert selling

a console with an electric motor. Two other

electrically-driven acoustic machines of this

era are so far described in the CAPP pages:

the “Canadian” Electric Phonograph and the

Musicphone, both made in Ontario.

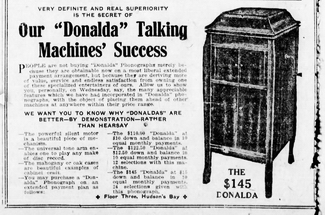

So who made these “Donalda” machines? The

only reason they existed at all is likely because of

the exorbitant cost of shipping similar machines

westward from their point of manufacture in

southern Ontario. Of course, Hudson’s Bay

would not have built the machines themselves,

but merely branded those of another supplier,

much like the company buys then sells Beaumark

appliances even today. There is a long history

of retail re-branding such as Sears Silvertone

phonographs, Kenmore appliances and Eaton’s

Viking appliances.

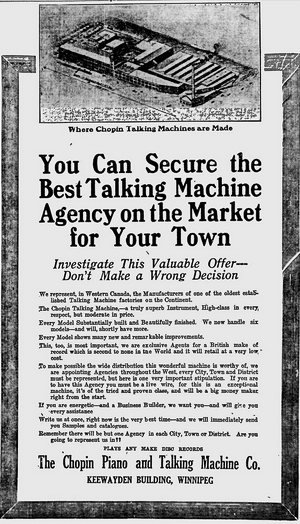

Two possible manufacturers have been uncovered

to date. Moogk, in Roll Back The Years (page

64) reads, “...Winnipeg became the focal point

for distribution in the growing Western Canada

Market [for phonographs]. The Chopin Piano

and Talking Machine Company handled the

Chopin Talking Machine from its offices in the

Keewayden Building, and the Melotone (‘The

sweetest of them all’) was available from the

Melotone Talking Machine Co. Ltd. at 235 Fort

Street.”

|

|

The “electrically operated console”,

Calgary Daily Herald,

September 10, 1923, pg. 16.

|

|

|

|

Winnipeg Tribune, Feb 22 1921, pg. 12.

|

|

|

“Puritan” model, Calgary Daily Herald,

January 5, 1923, pg. 24.

|

|

|

I’ve found 1917, adverts for “Chopin” published

in Regina, Saskatchewan and Calgary, Alberta

trumpeting “one of the oldest established Talking

Machine factories on the Continent”, apparently

looking for distributors of “this wonderful

machine” throughout “The West, every City,

Town and District”. But so far no further

information has been uncovered on possible

sources for the “Donalda” machines.

|

|

Possible manufacturer of the “Donalda”?

The Morning Leader,

Mar 24, 1917, pg. 17

(Regina, Saskatchewan).

|

|

|

So here’s to the “Donalda”, first physical

Canadian phonograph we’ve so far uncovered

west of Ontario and maybe Canada’s answer to

the “Melba”, in more ways than one!

[Late addendum: new information shows up constantly. After I

wrote the above, an email from Betty Pratt sent

me looking at a new source and now I have

uncovered references to the following machines

sold in western Canada and are unknown in the

east—further help on them would be appreciated:

Larktrola, Euphonolian, Strolla and Sovereign.

Also found was a one-line reference to a “Chopin

Phonograph” for sale by the Winnipeg Piano

Company in 1917.]

References

- Pauline Donalda career entry in the Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Pauline Donalda "quick biography" in the Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Pauline Donalda, The Life of a Canadian Prima Donna, by Ruth C. Brotman, The Eagle Publishing Company, 1975.

- The Compleat Talking Machine: A Collector's Guide to Antique Phonographs, by Eric L. Reiss, Sonoran Publishing, 1998, rear cover.

- Biography of Lord Strathcona from the Hudson's Bay Company.

- Lord Strathcona's entry in the Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Roll Back The Years, by Edward Moogk, National Library of Canada, 1975, pg. 132-133.

- Ibid, pg. 64.

- Saskatoon Phoenix, August 11, 1922, pg. 12.

- Calgary Daily Herald, October 16, 1922, pg. 18.

- Ibid, January 5, 1923, pg. 24.

- Ibid, February 3, 1923, pg. 24.

- Ibid, September 10, 1923, pg. 16.

|