|

Not Mr. Edison's Talking Machine

by Arthur E. Zimmerman and Betty Minaker Pratt

|

|

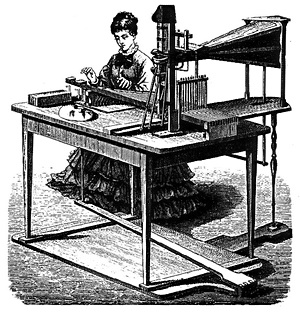

Shown is a female operator at the keyboard of Faberís "Euphonia", a mechanical

speech synthesizer that spoke through moving lips in a sepulchrous, creepy monotone

and inspired Bellís work toward his telephone.

|

|

|

There are talking machines, and then there

are machines that talk. Perhaps the first

known use of the term "talking machine"

in the U.S.A. was in the Quincy, Illinois,

Herald in 1844 (1), to describe Joseph Faberís

mechanical speech synthesizer that was played

with a keyboard and foot-pedals, like an organ.

Possibly the later uses of the term by Edison and

The Victor were appropriated from Faberís well-known

contrivance.

There had been much earlier attempts to fabricate

devices that could approximate human speech.

The natural philosopher and bishop Albertus

Magnus (c. 1206-1280) constructed a head

that moved and spoke, but his former pupil,

St. Thomas Aquinas, destroyed or hid it as an

abomination and a blasphemous challenge of

the Divine Order. Roger Bacon (1214-1294), an

English monk and the inventor of eyeglasses, is

also supposed to have made such a contraption

and in the 1770s Abbť Michal in Paris, Friedrich

von Knaus in Austria and a Mr. Kratzenstein

in St. Petersburg demonstrated their speaking

machines. Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen devised

a sort of talking pipe-organ (1769-91), which was

improved upon by the British electrical pioneer

Sir Charles Wheatstone (1802-75), but Faberís

"Euphonia" was deemed much better.

We stumbled upon the "Euphonia" story in

The Liberal of Richmond Hill, Ontario, June

17, 1886 (2), describing the demonstration of an

apparatus mounted on a gilt table, involving a

bellows for lungs, an artificial larynx, teeth, a

tongue and moving lips of black India rubber

mounted in a face mask, controlled by a keyboard

and able to say "mama", "papa" and an assortment

of female names.

|

|

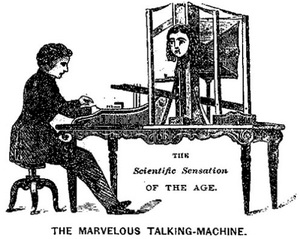

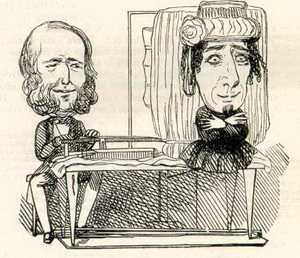

"The Marvelous Talkng Machine": Probably the second Prof. Faber

(husband of Joseph Seniorís niece) at the keyboard, operating the

"Euphonia".

("Illustrated History of Wild Animals and

Other Curiosities Contained in P.T. Barnumís Great Travelling Worldís

Fair...." by William C. Crum, Wynkoop & Hallenbeck, New York, 1874)

|

|

|

At the end of the show, the

"Euphonia" said, in a doleful, monotonous

tone, "Iím very tired. Thank you, gentlemen.

Adieu". This report is anachronistic because, by

1886, Edisonís Perfected Phonograph had been

demonstrated and improved and the "Euphonia"

and all of its bits and pieces had disappeared from

history.

The story is sketchy, with variants, but it looks

as if Joseph Faber (c. 1800 - 1860s) was born

at Freiburg im Breisgau near the Black Forest,

studied at the Polytechnic in Vienna, most

interested in mathematics, astronomy and music.

While convalescing from an illness, doing woodcarving,

he read von Kempelenís work (3), went

back home and spent years building his prototype

of the speaking machine. He showed it in Vienna

in 1840 and to the King of Bavaria in 1841 (4),

but it excited little interest. He emigrated to the

United States (5), showed his invention in New

York City in 1844 (6) and then in Philadelphia,

where scientist and Director of the U.S. Mint

Robert M. Patterson saw it and was impressed.

Patterson even spoke about the machine to the

American Philosophical Society in May, 1844

and tried to raise financial backing for Faber (6)

but, discouraged, Faber destroyed his machine.

Patterson then accompanied fellow-scientist

Joseph Henry to Faberís workshop where he was

re-assembling his talking automaton, this time

with a female face. Henry was greatly impressed,

thought it superior to Wheatstoneís talking

figure (7) and encouraged Faber to demonstrate

its capabilities at the Musical Fund Hall in

Philadelphia in December, 1845. That showing

was another failure.

|

|

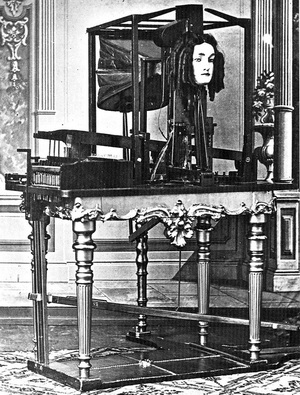

A photographer from the Mathew Brady studio, possibly Mathewís

nephew, captured an image of Joseph Faberís "Euphonia" at

Barnumís Museum in New York, circa 1860.

|

|

|

Around this time, Phineas T. Barnum, looking for

a fresh novelty, named the speaking automaton

"Euphonia" and took Faber to London (6, 9, 10),

where he showed the machine at the Egyptian

Hall in 1846. The "Euphonia" got the admiration

of the Duke of Wellington and satirizing by

Thackeray in Punch (11). Thackeray opined that

assistants could henceforth key-out pastorsí

weekly sermons for the congregations and that

Scottish parliamentariansí speeches could finally

be understood through the "Euphonia". Joseph

Henry and later Faber conjectured connecting

a "Euphonia" at either end of Samuel Morseís

marvel to give the world a talking telegraph.

It turns out that Melville Bell also saw the

"Euphonia" in London and that later influenced

Melville and his son Alexander Graham in their

work on speech synthesis.

The "Euphonia" actually worked. Witnesses said

that it had a "hoarse, sepulchral voice...as if from

the depths of a tomb" and some thought that there

had to be a small person hidden somewhere inside

it. In London, the "Euphonia" sang "God Save

the Queen" in its other-worldly flat voice. The

Illustrated London News was most impressed (10),

reporting that "The automaton is figured like a

Turk, the size of life, and of kit-cat proportions

(i.e. half-length portrait), reclining against some

pillows. Every portion of the machine is, however,

thrown open to the inspection of the company,

and its framework is moved about the room".

They noted that, since Faber was a German, "the

figure converses more fluently in that language

than in our own, but it is equally capable of

speaking French, English, Latin, Greek, and even

whispering, laughing and singing".

People remarked that they could even feel the

breath of the "Euphonia" emanating from the

India rubber lips set into a "stoney-eyed" mask

of a female face, but that was because the basic

driver of the apparatus was a large bellows

operated by a foot-pedal. The compressed air

was driven through a collection of reeds, whistles

and whoopie-cushion-type resonators, modified

by various shutters and baffles, and these were

controlled individually or in concert by a board

of 16 or 17 keys or levers.

|

|

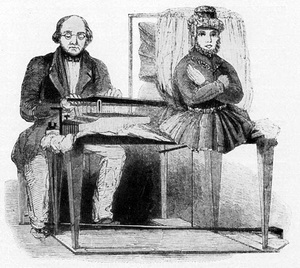

Inventor Joseph Faber Senior, operating his speaking automaton from

the keyboard like an organ. The early model was arranged to look like

the face and torso of a Turk, a reference to another of Baron Wolfgang

von Kempelenís contraptions, a famous chess-playing figure. The latter

was a hoax, so the public was very suspicious of Faberís machine,

looking for a person hidden in the open framework or a speaking tube

through the floor.

("Illustrated London NewsĒ, August 1846)

|

|

|

The 16 or 17 elemental

sounds could be combined to sound out words

and phrases. The Liberal revealed that "the letters

represented on the keyboard were A, O, U, I, E, L,

R, W, F, S, Sh, B, G, and these were declared by

the professor to be all that was necessary, with the

judicious opening and closing of the rubber lips

to produce all combinations of sounds known to

the phonetic economy" (2). The speaking was, not

surprisingly, slow and deliberate.

Faber was described as a sad-faced be-spectacled

man, gloomy and taciturn, dressed in respectable

well-worn clothes that bore signs of the

workshop....not too clean, and his hair and beard

"sadly wanted the attention of a barber" (9).

After taking Faber to London for the Egyptian

Hall exhibition, Barnum showed it at his

American Museum of curiosities in New York

City, where Mathew Bradyís studio photographed

it, c. 1860, and later in his touring circus.

Faberís talking machine was still being shown in

Barnumís Circus when it played the Exhibition

Grounds on Grenville Street in Toronto in August

1874. The Toronto Mail (12) noted large crowds

around the machine, but observed that it must

have had a cold or a dislocated jaw because all of

its words sounded monotonous and similar.

A retrospective in The London Times in 1880

(4), said that Faber worked on his apparatus from

1815 to 1841, latterly with his nephew Joseph

Faber, demonstrated it to the King of Bavaria

and then died (by suicide in the 1850s or 1860s),

bequeathing it to his nephew. Altick said that it

was the husband of Faberís niece who toured

with the "Euphonia", calling himself Professor

Faber (13).

|

|

The 1846 "Punch" cartoon, showing the radical Tory MP Lord

George Bentinck, who had previously spoken very little in Parliament,

making the "Euphonia" finally address the House for him, though still

through Benjamin Disraeliís face.

|

|

|

In 1887, The New York Times reported that

Professor Faberís wife, Mrs. Mary Faber who

had operated the keyboard in years of touring,

threatened with eviction, attempted suicide in

her New York City apartment by taking the

insecticide Paris Green (14). Drifting in and out of

consciousness, she indicated a satchel containing

the "Euphonia" and wanted it sold to pay the rent.

It turns out, however, that this Mary Faber was

45 years old in 1887, too young to be Joseph Sr.ís

wife, so it is not clear whether this Mrs. Mary

Faber was Joseph Seniorís wife or his niece.

Around 1863, perhaps reminded of the

"Euphonia", phoneticist Melville Bell took young

Alexander Graham to meet Wheatstone, who

showed the Bells his contraption, and A.G. and

his brother built their own speaking automaton.

It had nasal cavities, a larynx, a soft palate and

a laterally articulating tongue. This experiment

in speech mechanics and his interest in teaching

the deaf eventually led to A.G.ís shifting from

mechanical to electrical technology, to his

"harmonic telegraph"and thence to the telephone.

Faberís "Euphonia" did not excite much interest

among theologians but the clergy flocked to see

and hear the results of Edisonís further shifting

of technology, continuing to be shocked and

appalled that a mortal aspired to re-create a basic

element of the sacred human spirit and violate the

Divine Order. To be fair, however, it was Faberís

machine that could synthesize the human voice,

whereas Edisonís tin-foil impious contraption

would speak only if addressed first, and then quite

firmly.

General Sources

- Quincy, Illinois Herald, February 9, 1844.

- "A Talking Machine" in The Liberal of Richmond Hill, Ontario, June 17, 1886, p. 6.

- Kempelen, Baron Wolfgang Ritter von, "On the Mechanism of Human Speech", Vienna, 1791.

- "Talking Machine", London Times, February 12, 1880.

- "Biography of Joseph Faber Senior, Inventor of the 'Euphonia' Talking Machine, in Phonozoic Text Archive, Document 094.

- "Talking Head" by David Lindsay in The Magazine of Invention, vol.12 #3, Winter 1997, and Talking Head.

- "Joseph Henry and the Telephone" in The Joseph Henry Papers Project by Frank Rives Millikan.

- "Joseph Faber and the Amazing Talking Machine', in The Peerless Prodigies of P.T. Barnum".

- "Joseph Faber's Talking Euphonia"in Irrational Geographic.

- "The Euphonia, or Speaking Automaton", Illustrated London News, July 25, 1846, p. 59.

- "The Speaking Machine", attrib to Thackeray, Punch, July-Dec. 1846, p. 64.

- "Barnum's Circus", The Toronto Mail, August 4, 1874, p. 4.

- "Shows of London" by Richard D. Altick (Harvard Univ. Press, 1978, p. 356).

- "The Talking Machine Was There", The New York Times, July 24, 1887, page 9 - 6.

Thanks to Brenda Hicock, M.L.I.S. City of

Vaughan Archives.

|