|

Edison in Toronto

by Robert W. Gutteridge

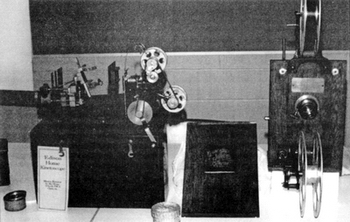

Robert's Rare 1912 Edison Home Kinetoscope (left) and 1898 Projecting Kinetoscope (right) were on display.

|

|

The following account is an abridged version

of a lecture/slide presentation given to the

CAPS' meeting on October 23, 1998. The

content is taken from a forthcoming book of mine,

Magic Moments: First 20 Years of Moving

1999. The material focuses on those aspects of

Edison's contributions to cinema as they directly

affected the coming of moving pictures to Toronto.

The first moving-picture device connected to

Edison which arrived in Toronto was his "peep-

show" Kinetoscope, a viewing device that allowed

only one person at a time to see a very short film

presented in a cabinet. Visitors to the 1894

Toronto Industrial Fair (now known as the

Canadian National Exhibition) were the first in the

city to have the opportunity of seeing moving

pictures beginning September 3. The Evening

Telegram announced on August 10: "Edison's

latest marvellous invention, the kinetoscope, will

be shown reproducing forms and scenes in motion,

just as the phonograph reproduces the living

voice." Thus, Edison's interest in moving pictures

was directed toward furthering his phonograph

machine.

Among other duties, William Kennedy Laurie

Dickson was the official photographer to

Edison's organization and it was logical that

Edison should give him the task of working out his

ideas for sequence photography. After

experimenting with up-to fifty-foot strips of

flexible Eastman film and a new camera, with a

vertical film feed, taking a 35mm-wide film band,

Edison decided on the commercial introduction of

the Kinetoscope in June 1892.

Early in the spring of 1894, ten machines were

shipped across the Hudson River to Andrew

Holland, who, along with his brother George, were

eastern agents of the Kinetoscope

Company (founded by Raff & Gammon).

The ten Kinetoscopes reached them on April 6.

On April 14, they opened the first Kinetoscope parlour at

1155 Broadway, New York City.

Display of rare Edison projectors

|

|

The brothers carried out further exploitation

in Toronto after the Industrial Fair by opening a

temporary Kinetoscope parlour commencing

December 10 in Webster's ticket office, located on

the northeast corner of Yonge and King streets.

Webster's was, most likely, chosen because

of its prime site — the business and entertainment heart

of Toronto — and being able to take advantage of

the constant flow of traffickers purchasing

steamship tickets or wishing to send telegrams.

Rumours percolated that Raff & Gammon, the

Kinetoscope representatives, were impatient since

the "peep-show" Kinetoscope business was

dragging and decreasing. The "peep-show" parlor

men were clamoring for a machine that would

project the picture life size on a wall. The

Kinetoscope customers looked to Edison for a

perfected machine. But Edison was still unmoved.

Nothing important had been done at his West

Orange plant toward perfecting a "screen

machine" and it seemed that nothing was going to

be done.

After leaving Edison, Dickson soon became a

founder of the K.M.C.D. Syndicate (later to

become The American Mutoscope and Biograph

Company). It planned to develop a peep-show

device that was based on the flip book idea.

Thus, the Mutoscope was born. Much larger pictures

had to be created since, unlike the Kinetoscope,

the Mutoscope card-wheel pictures were to be

viewed by reflected light as in looking at an

ordinary photograph. A greater area was necessary

to compensate for the loss of light. A new camera,

whose mechanism differed from Edison's

Kinetograph camera in order to avoid patent

infringement, was created mainly by Dickson.

The Mutoscope was ready sometime in 1895 —

likely September.

The coming of the cheaper Mutoscope

promised to wipe out the business of the

cumbersome and costly Kinetoscope. But "Lady

Luck" entered just in time in the form of a

telegram from Thomas Armat of Washington D.C.

in which he promised Raff & Gammon perfected

projection on screen. They were interested but

skeptical. However, after Gammon's visit to

Washington where he witnessed the success of

Armat's projector, they carefully persuaded Edison

to build 80 machines and Armat to allow the

machine to be promoted under the 'Edison' name.

Thus, the so-called 'Edison' Vitascope was

launched.

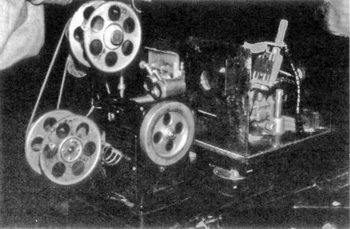

Closeup of the 1912 Edison Home Kinetoscope

|

|

Neither Edison nor Armat was especially fond

of the arrangement, but it was accepted by them at

the dictation of Raff as a matter of commercial

expediency. This settlement bought Edison time

to play catch-up with others as he worked to

develop his own projecting apparatus.

Meanwhile, the Vitascope's opening at

Robinson's Musee Theatre, 91 Yonge Street (east

side just north of King Street), August 31, 1896,

gave the Musee the honour of presenting the first

projected moving-pictures to Torontonians.

But only by one day, for the Lumiere

Cinématographe opened the next day at the Industrial Fair. The

first series of films may have included:

SHOOTING THE CHUTES AT CONEY

ISLAND; THE KISS — featuring May Irwin and

John Rice; and THE BLACK DIAMOND

EXPRESS (a locomotive). For certain, exhibited

was La Loie Fuller doing BUTTERFLY DANCE,

one of those serpentine dances; it was the hand-

painted colour version. The Vitascope remained at

Robinson's until October 10.

It was natural enough that it should now in the

autumn of 1896 appear that Edison's only chance

to make money quickly on the motion picture was

as a manufacturer of picture machines, which he

was to sell on the open market rather than tying

them up in territorial agreements as was the

practice of the day. Besides, the business-minded

Edison had control of the camera that produced all

those films that were necessary for an exhibitor

owning one of his machines. In November 1896,

the break between Edison and Raff & Gammon

occurred. Eighty Armat Vitascopes had been

manufactured by Edison and delivered. The time

was right for Edison to introduce his first "screen

machine" — the Edison Projecting Kinetoscope.

This action immediately made a breach between

Raff & Gammon and Edison, and created tension

between Raff & Gammon and Armat, when they

were expected to defend the Vitascope against

Edison's invasion of the projection field. Here

was the beginning of the strife, which made the

motion picture a battle ground for the next twenty

years. There was an ultimate victory far ahead for

Armat, whose fight became one of the incidental

campaigns of the general conflict. Edison further

undercut Raff & Gammon by selling his films for

his own projector at a lower price that Raff &

Gammon were offering to their Vitascope

customers. By the end of 1896, the Vitascope

enterprise, like the "peep-show"

Kinetoscope, was no more.

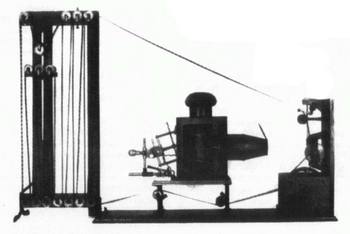

Inventor Thomas Armat’s Vitalscope from the

October 31, 1896 issue of Scientific American

|

|

Edison's first model Projecting Kinetoscope

made its Toronto debut on October 5, at the

Toronto Opera House, 25-27 Adelaide Street west,

south side, a few doors west of the prestigious

Grand Opera House. But it was advertised under

the name "Kinematographe."

The Edison "improved" '97 Model Projecting

Kinetoscope opened January 25, 1897 at

Robinson's establishment, whose name had

changed in November 1896 to Robinson's Bijou

Theatre. This time the machine was announced as

the new Motograph. It was quite possible that

Edison had absolutely nothing to do with the

"Motograph" label for it was quite a common

practice then for the true identity of a projector to

be replaced. For example, the Majestic Theatre

advertised its machine as the "Majestiscope."

At the Bennett theatres, their machine was publicised

as the "Bennettograph."

The next Edison situation involved a film.

PASSION PLAY moving-pictures were presented

free, nightly, in Munro Park, beginning July 9,

1900, for two weeks. Whose version was shown?

Three were produced in the period 1897-98.

I believe that the version at Munro Park was the one

by Rich G. Hollaman and Albert G. Eaves.

Trouble arose when someone leaked word to the

New York Herald, which published the fact that

the Hollaman-Eaves pictures were not taken at

Oberammergau, Germany, but right in New York

City on the roof of the Grand Central Palace

Theatre, December 1897. Edison considered that

the Eden Musee, New York, was using an outlaw

film. The films, to Edison, were obviously

produced with a camera that did not bear the

authority of Edison. Edison had sold no cameras

and never intended to do so.

The case against the Musee appeared to be

definite. In the face of this, Hollaman was

pondering on the problem of putting prints of his

PASSION PLAY on the market. Frank Maguire of

Maguire & Baucus, handlers of Edison films, gave

Hollaman some advice: "If you turn your negative

over to Edison and buy your films from him,it

might be different." Hollaman took the advice,

and further legal action ceased. Many prints were

leased and copies under Edison's name went

abroad, and covered the world of the motion

picture.

Jeremiah (Jerry) Shea of Buffalo, New York,

opened his Yonge Street Theatre on September 6,

1899 on the same site as Robinson's Bijou

Theatre. By December 1903, Shea made an

arrangement with the Kinetograph Company,

which did not make its own moving pictures but

rather was dependant upon the good will of

Edison's Kinetograph Department, and really

represented an extension of the Edison company

into the field of exhibition. This agreement stated

that all the Kinetograph Company's

important moving pictures were to be shown in Shea's

theatre before they were sent to any other theatre

in Canada. One such film was by Edwin S. Porter,

an Edison employee who was to make an

important impact on the history of cinema through

his focus on narrative or story films.

His popular film THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY was first

shown in Toronto at Shea's Theatre during the

week of December 14, 1903.

Inventor Model 1897

Edison Projecting

Kinetoscope

|

|

Starting the week of March 24, 1913 Shea

(who, had since relocated his establishment — now

called the Victoria Theatre — at the northeast

corner of Richmond and Victoria streets) offered

Torontonians an opportunity of experiencing the

new Edison synchronous sound process — the

Kinetophone, after his 1895 invention. The

Toronto World wrote of the films: "The first

picture is a description lecture on the kinetophone.

The lecturer appears in the picture, and, as he

gestures and as his lips move, the words are

distinctly heard. He explains the invention:

"Ladies and gentlemen, a few years ago Thomas

A. Edison presented to the world the Kinetoscope

and today countless millions of people in every

section of the civilized world are enjoying the

Phonograph. It remained for Mr. Edison to

combine two great inventions in one that is now

entertaining you and is called the Kinetophone.

The Edison Kinetophone is absolutely the only

genuine talking picture ever produced."

Examples are given. A man is seated at the piano and plays;

a vocalist approaches and sings 'The Last Rose of

Summer,' and a violinist plays a solo. Barking

dogs are seen and heard. A second reel is shown,

called the Edison minstrels.

How was the Kinetophone apparatus installed

in a theatre, such as Shea's? The phonograph,

placed behind the screen, used a cylinder record

nearly a foot in length and four or five inches in

diameter and a horn and diaphragm considerably

larger than those of home phonographs.

It determined the speed, being connected through a

string belt, to a synchronizing device at the

projector. The belt pulleys were about 3 inches in

diameter. The belt passed from the phonograph up

over idler pulleys, and overhead, back to the

projection booth. The synchronizing device

applied a brake to the projector and the brake-shoe

pressure depended on the relative phase of the

phonograph and projector, increasing rapidly as

the projector got ahead in phase. With an even

force on the projector crank, normal phase relation

was maintained. The projectionist watched for

synchronism and had a slight degree of control by

turning the crank harder if the picture were

behind or easing it off if it were ahead.

Edison's dream finally came true, but he was to

awaken with a sharp jolt. The system that had

worked well in the controlled conditions of the

Edison laboratories or in the Bronx studio,

developed unexpected imperfections when

transferred to the theatre. The Palace, in New

York City, was one of several theatres where the

Kinetophone lost synchronization or broke down

completely. Audiences hissed Edison's talking

pictures off the screen, and Keith-Orpheum paid

the Edison Company to terminate the contract and

withdraw its talking pictures. It did not appear

that such problems occurred during the run at

Shea's Victoria.

In the wake of this experience, Edison no

longer considered sound movies worthy of further

improvement or experimentation, and persistently

ridiculed or underrated the efforts of other

inventors to accomplish what he had failed to do

with the Kinetophone.

Sources:

- John Barnes, The Rise of the Cinema in Great

Britain (Bishopsgate Press Ltd., London,

1983)

- Brian Coe, The History of Movie

Photography (Ash & Grant, London, 1981)

- Raymond Fielding, ed., A Technological

History of Motion Pictures and Television

(University of California Press, Berkeley,

1974)

- Harry Geduld, The Birth of the Talkies

(Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1975)

- David S. Hulfish, Motion-Picture Work

(American School of Correspondence,

Chicago, 1913)

- Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows (McGill-

Queen's University Press, 1978)

- Peter Ramsaye, A Million and One Nights

(Simon & Schuster, Inc., New York, 1927)

- Various Toronto daily newspapers—Globe,

Mail and Empire, Evening News, Star, Evening

Telegram and Toronto World.

|